Clarence Buckingham Fountain, Grant Park. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, 2017.

No matter whether we’re having a frigid or very warm spring in Chicago—or—as we’ve experienced this year, a combination of both, the “switching on” of the Buckingham Fountain is one sure sign that summer is nearly here. The annual event has become even more meaningful during this COVID era when we are all seeking outdoor destinations and activities. This year’s official celebration to “turn on” the fountain took place a couple of weeks ago, on May 14, 2022.

Edward H. Bennett. Courtesy of Burnham & Ryerson Art and Architecture Archive, Art Institute of Chicago.

Completed in 1927, the Clarence Buckingham Memorial Fountain was conceived and designed by architect Edward H. Bennett (1874-1954). Born in England, Bennett moved to San Francisco as a young man, and decided to become an architect. After graduating in 1901 from the École des Beaux-Arts, the famous French architecture school, he won an award to travel throughout Europe. The following year, Bennett moved to New York, and began working for George B. Post, who was among the small group of architects that Daniel Hudson Burnham had called upon to create buildings for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. In 1903, Burnham was working on a design competition for new buildings at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and found himself short-handed. Post agreed to “loan” Bennett to Burnham for the project. The two architects worked so well together that it quickly became clear that Bennett would not be returning to Post’s office.

Revised Preliminary Plan for Grant Park, Olmsted Brothers, 1903. Chicago Park District Records: Drawings, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

Since the mid-1890s, Burnham had been working on sketches, studies, and schemes for improving Chicago’s lakefront. Burnham wanted to enlarge Grant Park through landfill and create improvements to the public space that would reflect the “White City” design and “outrival Paris.” Department store magnate Marshall Field had provided the funds for a natural history museum that was operating out of the fair’s former Fine Arts Pavilion in Jackson Park. Field offered to fund the construction of a new museum building. Burnham proposed a magnificent Beaux Arts style structure to serve as the centerpiece of Grant Park. He envisioned that it would be surrounded by parterres, formal tree allées, trimmed hedges, fountains, and sculptures. (He also intended to include a couple of other buildings in the park.) In 1903, the South Park Commission hired the Olmsted Brothers to help realize this scheme.

Figure CX, 1909 Plan of Chicago, by Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett.

The development of Grant Park was held up by lawsuits initiated by Field’s business competitor, Aaron Montgomery Ward, who wanted to abide by early restrictions against buildings in the park. As the controversy dragged out in the courts, Burnham and Bennett worked together on additional plans to beautify Chicago’s lakefront. They devoted an entire chapter of their seminal Plan of Chicago to Grant Park. This chapter continued to show the Field Museum as the centerpiece of a formal landscape. Correspondence in the Edward H. Bennett Collection at Lake Forest College shows how close Burnham and Bennett had become during these years. In December of 1908, while Burnham was on a European trip, he wrote to Bennett, reminding him not to let anyone see the drawings in the Plan of Chicago until its publication. He also described his sightseeing adventures including the beautiful relics in “old Rome.”

Grant Park in the Early Spring of 1908. Report of the South Park Commissioners.

Ward won his final Illinois State Supreme Court lawsuit in late 1910. Over the next several years, the South Park Commissioners focused on creating an alternative site for the Field Museum at the south end of Grant Park, and the downtown lakefront area of Grant Park remained unimproved. When the park commissioners were finally ready to move forward on improving the site once again in the late 1910s, Burnham had been deceased for years. By this time, Edward Bennett was serving as consulting architect to the Chicago Plan Commission. In this role, he oversaw municipal efforts to implement the Plan of Chicago. Recognizing that Bennett was uniquely qualified to design Grant Park in a manner that would respect Burnham’s work, the South Park Commission hired his firm of Bennett, Parsons, Frost and Thomas to create a complete vision for the park.

Grant Park General View, Bennett, Parsons, Frost & Thomas. 1922.

Kate Buckingham. Photo courtesy of Findagrave.com.

Bennett proposed a large ornamental fountain to serve as Grant Park’s centerpiece—a monumental focal point that could convey the French Renaissance style without obstructing views of Lake Michigan. In 1924, philanthropist and art patron Kate Sturges Buckingham agreed to donate funds for an electrically operated decorative fountain. The gift was made as a memorial to her brother Clarence Buckingham (1854-1913), a banker and businessman who had served as a trustee and director of the Art Institute of Chicago. Bennett had at first suggested that the fountain could be created for approximately $300,000, but by the time the project was completed, Kate Buckingham had contributed over $1 million for the fountain and a fund for its perpetual care.

Edward H. Bennett recruited two Frenchmen to collaborate on the design of the fountain—sculptor Marcel Loyau and engineer Jacques H. Lambert. (Architect C.W. Farrier of Bennett’s firm was also deeply involved in the project.) The Latona Basin at Versailles inspired Bennett’s vision for the design of Buckingham Fountain. Its wedding cake shape with three basins of Classically-carved pink George marble is particularly evocative of the historic French model. Intended as a symbol of Lake Michigan, the Clarence Buckingham Memorial Fountain is substantially larger than the Latona. In fact, it is twice as large and re-circulates approximately three times more water than the Latona Basin.

Marcel Loyau and an unidentified man in front of Buckingham Fountain seahorses, 1926-1927. Courtesy of Ryerson & Burnham Art and Architecture Archive, Art Institute of Chicago.

The Buckingham Fountain uniquely conveys the Art Deco style through its bronze sculptures as well as the forms created by its water displays. Loyau sculpted four sets of stylized sea horses representing the states that border Lake Michigan. To create these artworks, the artist studied the sea horse collection at a zoological institution in Paris. The heads of Loyau’s sea horses tilt diagonally, and water spouts from their mouths. The impressive creatures sit amidst stylized bronze bull rushes and lilies. These Deco elements are quite different from the realistic frogs, turtles, and lizards and other figures that embellish the Versailles fountain.

Model of the Clarence Buckingham Fountain, ca. 1927. Courtesy of Ryerson & Burnham Art and Architecture Archive, Art Institute of Chicago.

Exhibitted at the Exposition des arts décoratifs in 1925, Marcel Loyau’s bronze sculpture Fontaine des Cygnes now sits at the center of a rondpoint at the Place Denfert Rochereau in the suburb of Boulogne Billancourt. Photo courtesy of Wikicommons.

Marcel Francois Loyau (1895-1936) was born in Onzain, France, and studied at Ecole des Beaux-Arts des Tours. He died at a young age and thus did not produce a large body of work. However, the Buckingham Fountain sculptures garnered him the Prix National at the 1927 Paris Salon. His public work in France includes Bronze de la Fontaine des Cygnes à Boulogne-Billancourt. While some of Loyau’s art reflects a Classical sculptural tradition, he also produced other Art Deco works, including sculptural embellishments for the Exposition Coloniale Internationale in Paris in 1931.

Buckingham Fountain Poster. John Buczak, artist. WPA, Federal Art Project, 1939.

Kate Buckingham made it clear that she wanted the lighting for Grant Park’s fountain to emulate soft moonlight. According to an early Chicago Park District brochure, “though advanced in years,” Miss Buckingham “worked night after night with technicians, trying out various colors… and adjusting the control of electric current” to create the desired effect. Originally, the light show involved 84 projectors and 560 incandescent bulbs. The lamps were covered in colored globes (clear, light rose, green, blue, and light amber) and the projectors had colored filters. A series of dimmers allowed for the blending of colors at varying intensities. (Today the fountain has a total of 800 bulbs.)

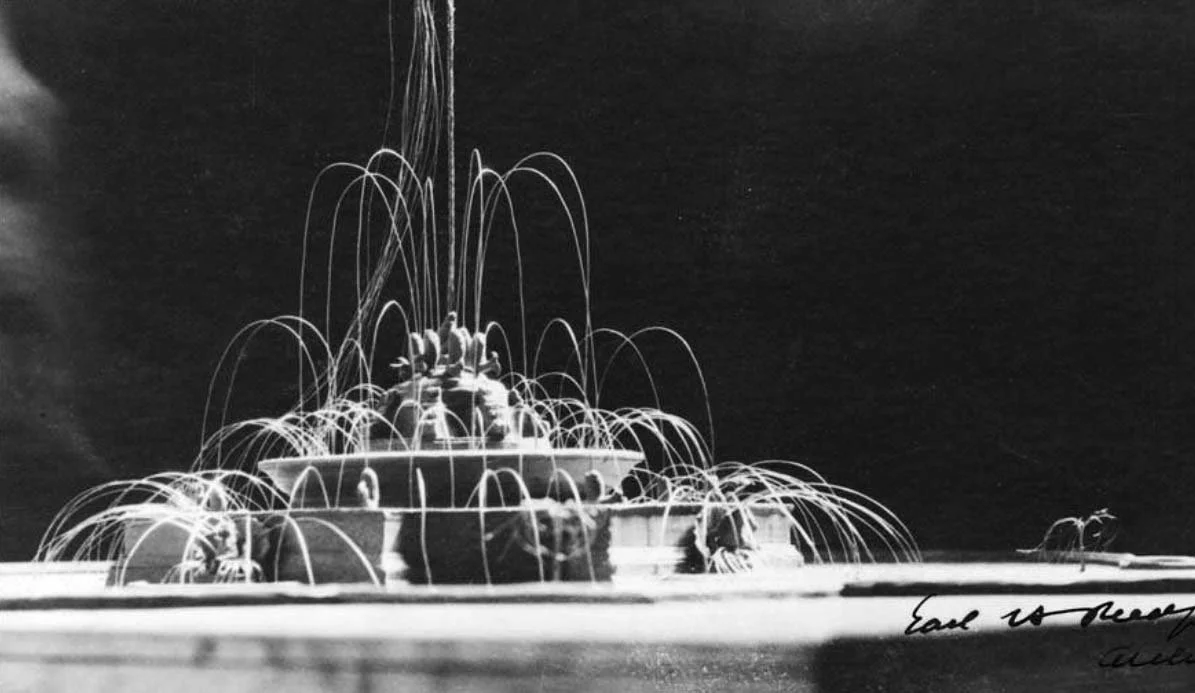

When completed in 1927, the fountain was really something of an engineering feat. With a lower pool that is 280 feet in diameter (nearly the size of a football field) and three progressively smaller basins that rise above the pool, the fountain holds 1.5 million gallons of water. During its major display, when water shoots to a height of 150 feet, the Clarence Buckingham Fountain recirculates more than 14,000 gallons of water per minute. In the late 1920s, the height of the spray was quite a marvel. A 1927 Christian Science Monitor article suggested that the Chicago monument reflects “royal fountains of the past, but built to a skyscraper scale.”

Buckingham Fountain during construction, ca. 1925. Chicago History Museum, DN-0081336.

A two-level underground pump house is located at the southeast corner of the fountain. The control room is at its upper level, and the three pumps that have powered the Buckingham Fountain throughout its history are located at the lower level. One of the pumps operates the fountain throughout the day, and the other two kick in during the major displays.

View of fountain overlooking pump house roof. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Winner of London’s 1953 “Most Perfect Secretary,” contest in the control room showing the dimmers and levers used to mechanically operate the fountain. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

The Buckingham Fountain was manually operated from 1927 through the 1970s. Throughout much of this period, two stationary engineers were in charge of running the fountain. Each worked a separate 12-hour shift. The engineers had rubber suits for wading into the water when they had to remove garbage blown in by the wind, change the angle of the lights, or make other minor repairs. During the fountain’s early years, major displays were provided only on Wednesdays, Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. In 1959, the Chicago Park District began presenting the major displays daily—first at 12:30 p.m. and again at 9:30 p.m. (The evening display of course included the light show.)

Buckingham Fountain brochure, ca. 1928. Courtesy of Chicago Park District.

The operations were first fully automated in 1980, when the Chicago Park District entered into a contract with the Honeywell Company. The computer was installed on site, but monitored remotely. For the first several years, the monitoring system was located in the Chicago suburbs. In the mid-1980s, however, Honeywell moved the monitoring system to a larger computer complex in Atlanta, GA. This arrangement continued until 1994, when the Chicago Park District undertook a major restoration which included a new local computer system. The Park District upgraded the Buckingham Fountain computer in 2013 with a non-proprietary Allen-Bradley PLC System. Today, all of the automation and monitoring takes place on-site, with remote alarm monitoring and notification.

Clarence Buckingham Fountain during the major display, 2009.

Over the years, the fountain has needed various repairs and restoration projects. These have included major masonry work in 1994 and upgrades to the plumbing, computer system, and surrounding landscape in 2009 and 2012. Most recently, the Chicago Park District repaired the beautiful bronze fencing around the fountain. Much of this work was funded by the endowment left by Kate Buckingham. It is inspiring to think about how important her enduring gift has been to Chicagoans and visitors over the years.