South Pond occupies the oldest part of Lincoln Park. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Stretching along more than six miles of the city's glorious lakefront, Lincoln Park is Chicago's largest park. It is also one of the oldest and most fascinating green spaces in the city. It began in 1860 as a 60-acre unburied portion of a public cemetery and evolved into a 1,200-acre park with six bathing beaches, three boating harbors, numerous gardens and natural areas, a zoo, and a conservatory, as well as a golf course and dozens of other athletic facilities. Throughout its history, the park's enlargement involved many complex landfill projects, with talented architects, landscape designers, and artists guiding its development. To illuminate the park's intriguing and multi-faceted history, I will be leading a six-part series at the Newberry Library on Thursday evenings between June 13th and July 25th. This seminar includes three in-class sessions and three walking tours. Please consider registering at newberry.org. In this blog post, I will share some of the park's early history with you.

The Couch Tomb is one of the few above-ground reminders of Lincoln Park's beginnings as a cemetery. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Dr. John H. Rauch. Photo courtesy of National Institute of Health "First Ten Presidents of the American Health Association."

City Cemetery was founded in 1837, just prior to Chicago's incorporation as a city. The State of Illinois had agreed to establish the public graveyard on a piece of federal land grant property on what was then the city's far north side. As the lakefront site's sandy soil and low wet swales offered poor burial conditions, local officials began receiving complaints about the cemetery soon after internments began in 1843. Despite such criticism, burials continued as the city grew rapidly. Disease outbreaks resulted in high death rates. Over a six-day period in 1854, more than 600 cholera victims were buried in the cemetery's Potter's Field. (For more information on the early cemetery see the Hidden Truths website.)

Dr. John Henry Rauch (1828-1894), a Chicago physician and public health advocate, began rallying support for the conversion of City Cemetery into a public park. He warned that cemeteries should never be located near densely populated areas and explained that this burial ground was especially problematic because bacteria and viruses from interred corpses could leach into Lake Michigan and contaminate the city's drinking supply. As a result of Rauch's campaign, the Common Council agreed to set aside the unburied 60-acre northern part of City Cemetery as parkland in 1860. For several years, this green space was known as Cemetery Park.

Plat of Cemetery Park, 1863, from Report of the Commissioners and A History of Lincoln Park, 1899, by I.J. Bryan.

Swain Nelson. Courtesy of Ed Gyllenhaal, Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA.

The small lakefront park received little attention until June of 1865, when the Common Council named the site as a memorial to Abraham Lincoln only a few months after the revered president's assassination. They allocated $10,000 for improvements to Lincoln Park. At the same time, Chicagoans were pressing the City to complete Union Park, a smaller West Side open space that had remained unfinished for over a decade. In response, the Board of Public Works ran advertisements in local newspapers soliciting plans for both parks in August, 1865.

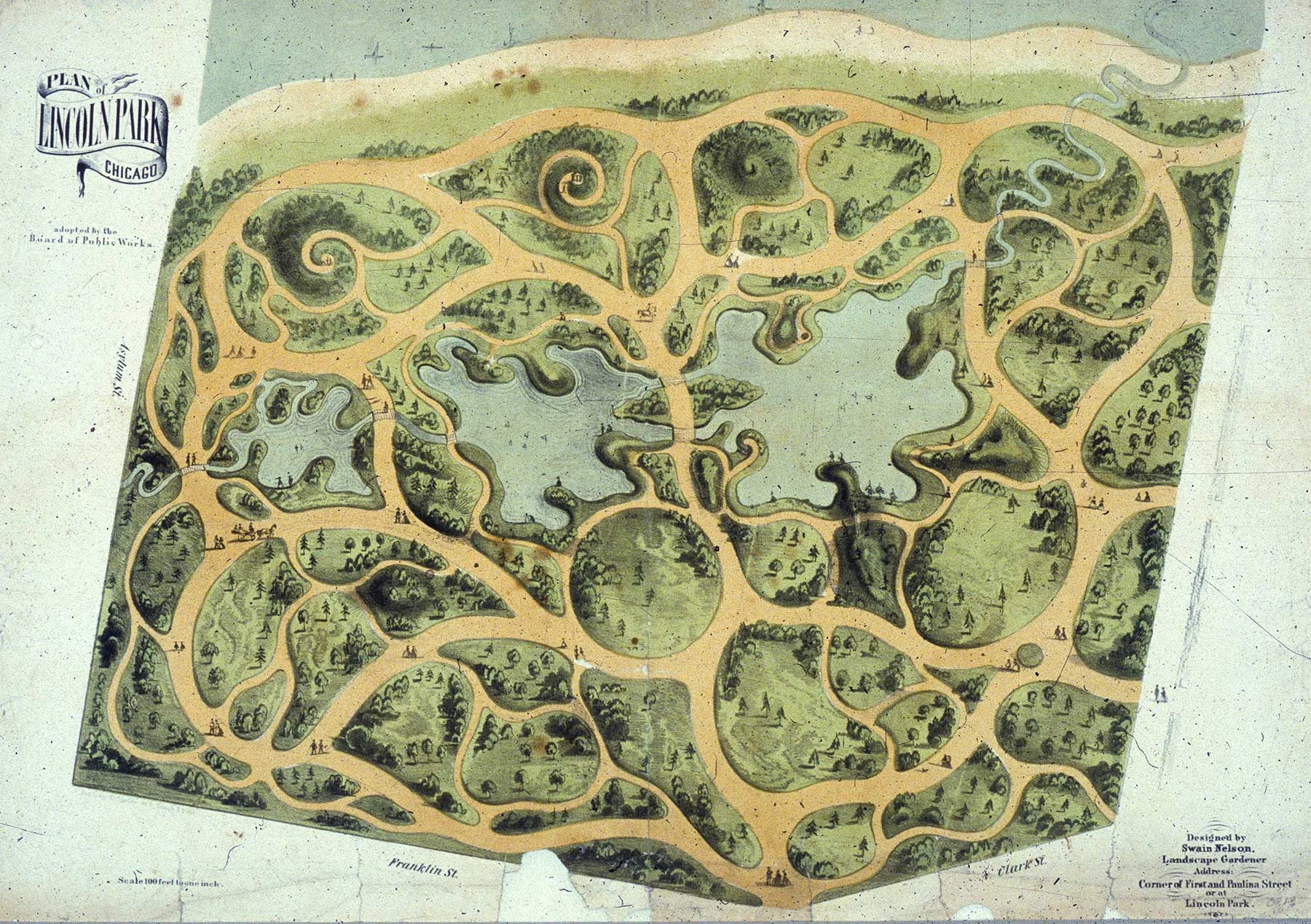

Swain Nelson (1828-1917), a Swedish immigrant landscape gardener, responded with a plan for Union Park. But, he did not prepare one for Lincoln Park because he thought that project would be awarded to the city engineer. The review committee so favored Nelson's whimsical Union Park scheme that they asked him to develop a plan for Lincoln Park. Nelson's original plan for Lincoln Park took advantage of the site's natural conditions. In the low area near the center of the landscape, Nelson designed a long serpentine lake. (The southernmost part of the waterway is today's South Pond.) Surrounding this artificial lake, he envisioned a series of hills—including the 35-foot-tall “Lookout Mountain”—as well as lawn areas with scattered trees and an intricate system of winding drives and paths. Nelson won a $200 prize, and city officials hired him to implement his plans for both Union and Lincoln Parks.

Original Plan of Lincoln Park by Swain Nelson. 1865, Chicago History Museum.

Nelson established his own nursery on land near Lincoln Park, importing elms, maples, and other shade trees from England and Scotland and also hauling in large trees from the woods on the outskirts of the city. In 1868, a New York Times story about Chicago described newly finished Lincoln Park as "Central Park in miniature." Nelson formed a partnership with his cousin, Olof Benson, and the two were tasked with making additional improvements to Lincoln Park, including building Lake Shore Drive in the early 1870s. (This original stretch of Lake Shore Drive aligns with the west side of the Lincoln Park Zoo parking lot.) Nelson & Benson's responsibilities included feeding and caring for the animals and fowl in the newly established Lincoln Park Zoo.

Lincoln Park Zoo, ca. 1900. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

As Nelson & Benson worked on the original 60-acre park, Dr. Rauch’s campaign to move the cemetery and expand Lincoln Park finally gained momentum. As a result, in 1869, the Illinois state legislature adopted three separate bills establishing the Lincoln, South, and West Park Commissions. While the three park commissions operated independently, the overall goal was to create a unified park and boulevard that would encircle the city. At that time, Lincoln Park’s new boundaries were expanded to Diversey Avenue (later Diversey Parkway) at the north and North Avenue at the south. Although many bodies had been disinterred and moved to other cemeteries by the mid-1870s, many others were left behind.

Plan of Lincoln Park and Boulevards, 1887. Chicago Park District Records: Drawings, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

Rustic Pavilion in Lincoln Park, from the Report of the Commissioners and A History of Lincoln Park, 1899, by I.J. Bryan.

By the early 1880s, Nelson & Benson began focusing on improvements to the parkland north of what is now Fullerton Avenue. Within this area, they created North Pond and used sandy soil from the dredging to fill the Ten Mile Ditch, an old drainage canal on the site, and to create a new hill called Mt. Prospect. A small rustic pavilion designed by architect Mifflin E. Bell was built on the northwest side of North Pond in 1883. The oldest extant building in Lincoln Park, the rustic pavilion originally stood next to an artesian well with a rocky grotto which fed the pond.

The Lincoln Park Commission built its first landfill extension in the late 1880s, after terrible winter storms threatened to wash away the entire eastern edge of the park, including Lake Shore Drive. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers prepared plans for a permanent system of breakwaters that would be built 500 feet off shore, on axis with Fullerton and North Avenues. The Commissioners decided to add 60 acres of new parkland on fill behind this breakwater. Plans called for lawns, a paved beach, and a new Outer Drive.

Map of Lincoln Park, 1903. Chicago Park District Records: Drawings, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

Postcard view of South Lagoon, ca. 1900.

While the project was underway, boaters asked that the plans be modified to include a “straight-away” for rowing. The Commissioners agreed, and a portion of the partially filled area was re-dredged to create what became known as the South Lagoon. This linear waterway remains a popular rowing course today.

By the late 1880s and early 1890s, several additional buildings and a number of sculptural monuments were erected in Lincoln Park. Among them is a Queen Anne style comfort station designed by architect Joseph Lyman Silsbee. Later nicknamed Carlson Cottage, the quaint building of pressed brick and rough-textured stones now serves as an office for the Lincoln Park Zoo volunteer gardeners.

Carlson Cottage. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Annette McCrea. Photo courtesy of the Cultural Landscape Foundation.

During the late 1890s, Chicago politics took a toll on Lincoln Park. A highly-respected park superintendent, John Pettigrew, was replaced by three politically-connected superintendents in rapid succession. Lincoln Park became known as a haven for patronage workers. A rare exception was Annette E. McCrea (1858-1928), one of the nation’s first female landscape architects. The wife of nurseryman Frank McCrea, Annette McCrea took over her husband's business after his death. In 1899, she wrote to the Lincoln Park Commissioners and asked to be appointed as the park’s first consulting landscape architect. The Commissioners agreed, and she began in that position in February, 1900.

Mrs. McCrea described her vision for Lincoln Park’s landscape in a Chicago Tribune article entitled “Plans Suggested for a Perfect Park.” Indicating that "under men's supervision" the park had become “too somber,” she reported that she would make “Lincoln Park a sylvan retreat.” Although her plans were widely praised, Mrs. McCrea was ousted after only six months.

Aerial view of Lincoln Park looking south from Foster Avenue, ca. 1935. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

During the 20th century, Lincoln Park continued to expand to the north through many additional landfill extensions. Without a doubt, that complex history will provide me with plenty of content for future blog posts. Other themes such as recreational changes over time, and Lincoln Park's world-class collection of sculptures and monuments certainly deserve my attention as well.