Washington Park’s Adventure Playland, 1970. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

Sometimes when you know someone as an adult and find out something about their childhood, it makes perfect sense. That was how I felt when I learned that Arnold Randall, who is now General Superintendent at the Forest Preserves of Cook County, loved playing in Washington Park’s Adventure Playland when he was a boy. Arnold first mentioned this to me when we worked together for the Chicago Park District in the early 2000s. I remember he seemed almost wistful when he described the unique playground that was nestled on an island in the park, only about two blocks away from his childhood home at E. 62nd Street and S. Champlain Avenue.

General Superintendent Arnold L. Randall. Photo courtesy of Forest Preserves of Cook County.

I recently asked Arnold about it again, and he said “it was such a fun place and unlike any other space in the park.” Someone else who grew up in the area posted on Facebook that the Playland was “dreamlike in its wild out-of-placeness.” I find it intriguing that this short-lived playground made such a strong impression on those who grew up nearby. So, I’d like to share the history of the Adventure Playland and its island location in Washington Park.

Children playing in “moonscape area” on Bynum Island in Washington Park, ca. 1970. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

Washington Park is, in essence, a living work of art. Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. (1822-1902)—the man widely considered the “Father of American Landscape Architecture” today—designed the greenspace as the Western Division of what was first known as South Park. Having prepared the original plan for New York’s iconic Central Park in the late 1850s, Olmsted and his partner, Calvert Vaux, began working in our area a decade later, on the design of the first planned community in the United States, Riverside, Illinois.

Olmsted & Vaux’s 1871 Plan of South Park. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Plan and Drawings.

In 1870, the newly-formed South Park Commission hired Olmsted & Vaux to lay out an expansive park that would serve the growing population along Chicago’s then-southern border. The following year, the firm completed the original plan for South Park, which included the 372-acre Western Division (Washington Park), the 593-acre Eastern Division (Jackson Park), and the 90-acre Midway Plaisance linking the two. (This year, Olmsted200 will be celebrating Olmsted’s contributions throughout the nation.)

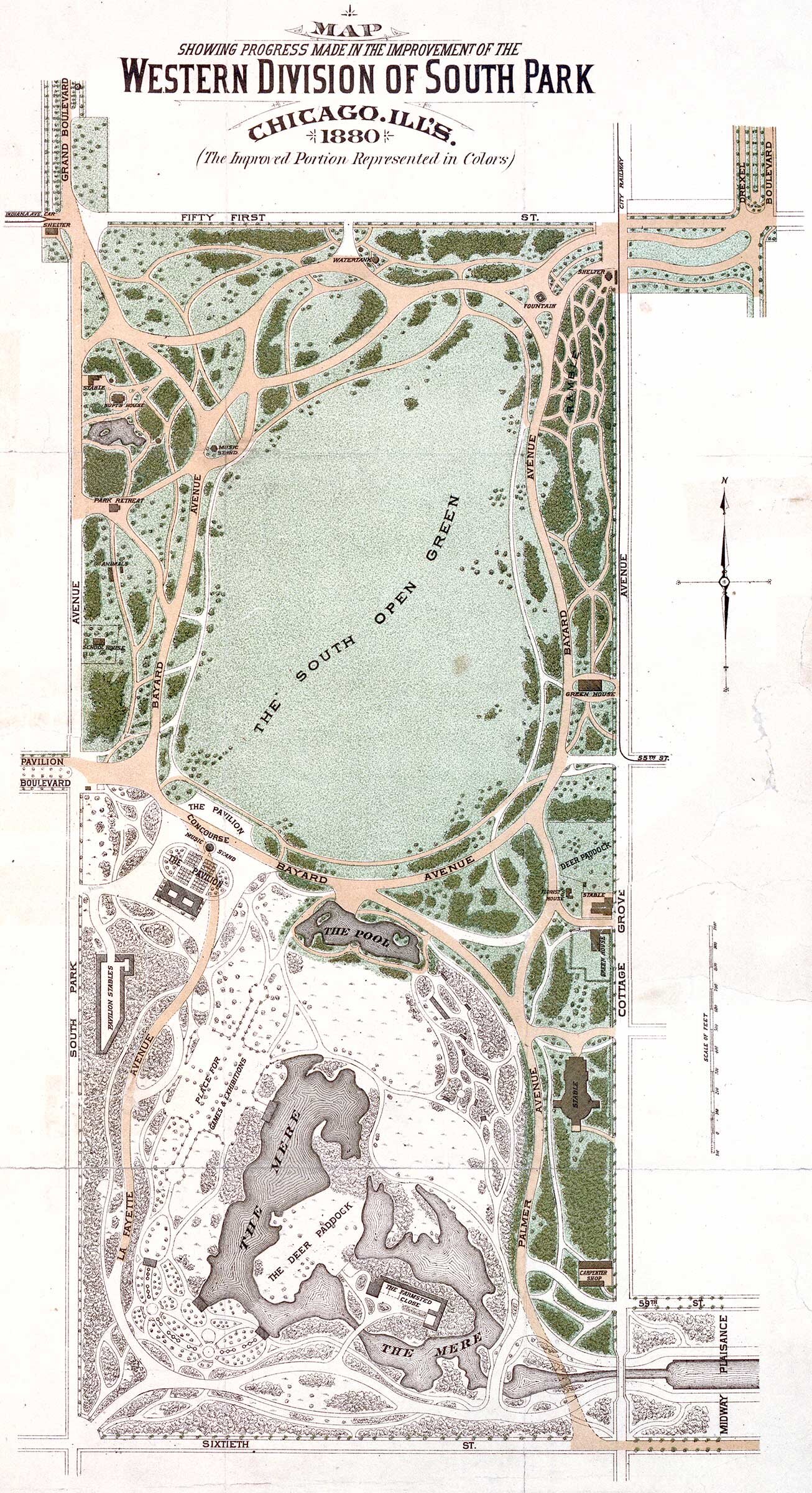

This plan shows the improvements made to Washington Park by 1880. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Plan and Drawings.

Sheep on Washington Park’s meadow, ca. 1910. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

Olmsted & Vaux’s Western Division (Washington Park) featured a broad lawn that they called the South Open Green. In the written report that accompanied their plan, the landscape architects explained that “…this meadow, with a grove of large trees surrounding it on all sides but one,” would have “sheep and cows grazing upon it,” and adults and children “playing here and there, as on a village green.” The plan also called for a seven-acre deer paddock. (Although the park would have sheep and deer, it never included cows.)

Olmsted & Vaux sought to create a pastoral landscape that would provide respite from the chaos of the rapidly-growing city. In their report, they suggested that, when entering the park from “either of two principal approaches from the city,” one would “find a view opening before him over a greensward without a perceptible break, considerably beyond the limits of the Open Ground itself,” and ending “…in a glimmer of water reflecting tall trees nearly a mile away.” The plan, in fact, called for two water features—a small oblong “Pool” and “The Mere,” a meandering waterway. The Mere curved around a small peninsula on which the deer paddock stood.

This view shows The Pool and The Mere to the south, ca. 1910. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

Rustic bridge, ca. 1910. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

During the late-1880s, a boat landing built on the west side of The Mere provided park patrons the opportunity to rent rowboats during the summertime. This was replaced by a Classically-styled boat house in 1902. Although boating was very popular in Washington Park, rowers were frustrated because every time they reached one end of the waterway, they had to turn their vessels around. To remedy the situation, in 1904 the South Park Commissioners excavated the connected end of the peninsula, extending the waterway so that boaters and ice skaters could make a full circuit. A rustic bridge provided access to the newly-created island.

By 1906 Washington Park had not had deer or sheep for decades. That year, the commissioners purchased a flock of about 100 South Down sheep and hired two park shepherds to tend them. As had been the case during the early years, sheep created “a picturesque effect” as they grazed the lawns throughout the park. Twice a day, park patrons enjoyed watching as a shepherd rounded up the sheep and guided them across the rustic bridge to their island pen. The commissioners maintained a flock in the park until 1921.

Aerial photograph of The Mere, island, and surrounding landscape on the southeast side of Washington Park, ca. 1935. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

Marshall F. Bynum, from “Services Set Thursday for M.F. Bynum, 57,” Chicago Tribune, November 4, 1969.

Roughly 50 years later, Washington Park’s island captured the imagination of Chicagoans once again. In 1969, the Chicago Park District (CPD) announced plans for an innovative “adventure playland” on the island that would accommodate hundreds of children and encourage imaginative play. The Commissioners soon named the island for Marshall F. Bynum, the first African American member of the Park District Board, a civic-minded businessman who had lived near Washington Park.

Designed by CPD landscape architects, the $750,000 island playground took advantage of its unique, natural-looking site. Specialized play areas were nestled into the landscape. As explained by a 1970 Chicago Tribune article entitled “Streets Take Second Place to Playground,” its many features included a creativity construction area with large blocks and Lincoln Logs that kids could use to “build their own forts and walls;” a moonscape with playground equipment emulating “rockets, satellites, space capsules, and space vehicles;” a section for fishing; slides, glides, swings and ziplines; and a pre-school area with an amphitheater for storytelling and puppet shows.

Washington Park Regional Playland Plans, Chicago Park District, October, 1969. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Plans and Drawings.

The CPD hired summer staff members to bring programming to the new Adventure Playland. Carol Marchand Neal, an art instructor who had recently completed her teaching degree, worked there for three summers. She was the only art teacher. Another staff member was a story-teller “who wore a floppy hat and a cape and really got into it.” Carol said the first summer was “a very good year,” because the playground had large, brand new Lincoln Logs, and plenty of art supplies. She told me that over the next two summers many of the Lincoln Logs had deteriorated and weren’t replaced, and her arts-and-crafts supplies weren’t as well-stocked.

Arnold Randall is one of the children depicted in this photograph that was published in the Chicago Tribune on August 26, 1975.

Arnold Randall began playing on Bynum Island around 1974. He remembers spending a lot of time on the rockets and satellites, tree houses, and slides. He and his brother loved bringing old cardboard boxes with them to the playground and using them to sled down the long metal slides. He said “we could go faster using the cardboard” and “sometimes the slides got pretty hot.” He recalls sliding across on the ziplines and he especially loved building structures in the Lincoln Log area.

Kids on ziplines in the Adventure Playland, 1970. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

Like many others, Arnold was disappointed when the playground fell into disrepair. He said this was “what was happening to my neighborhood overall in the 1970s and 80s. It was just another thing that was going away.” He told me that this negative trend actually inspired him. “As you know, I eventually managed the Southside parks, including Washington Park. The disinvestment I experienced like so many other Southside residents, added to my motivation to bring resources and reinvestment to these parks when I was in a position to do something about it.”

CPD outdoor camping on Bynum Island, 2009. Photograph courtesy of the Chicago Park District.

Although the CPD removed everything but the amphitheater in 1990, the district still runs special events on Bynum Island. The site is used for family camping and fishing programs and, from time to time, rope courses have been set up there. If you’d like to explore Washington Park with me, please stay posted. I will be giving a walking tours of several parks this summer in conjunction with the Chicago Park Library’s “From Swamps to Parks” exhibit. Details and registration information will be available in the near future.