Davis Square Fieldhouse. Photo courtesy of the Chicago Park District Department of Planning and Construction.

Last month, I wrote about “From Swamps to Parks: Building Chicago’s Public Spaces,” an exhibition I co-curated that recently opened at the Harold Washington Library. Exploring the tremendous vision, effort, and innovation that it took to create some of the city’s most beloved public spaces, the exhibit highlights six iconic park sites/themes—the lakefront, Lincoln Park Zoo, Soldier Field, the Garfield Park Conservatory, the Museum of Science and Industry, and the fieldhouse. On December 2, 2020, at 6:00 pm, I will give a virtual presentation relating to the exhibition. Presented by the Chicago Public Library and the Chicago Architecture Center, this program, “Building Chicago’s Public Spaces with Julia Bachrach,” is free and open to the public. (Registration is required. Waitlist spots will likely become available, .)

Fieldhouse and Wading Pool at Mark White Square, S. Halsted and W. 29th streets, Chicago, ca. 1905. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photograph.

During the virtual presentation, I will highlight two of the exhibit’s six themes—the Museum of Science and Industry and the fieldhouse. In November, I provided an overview of the history of the Museum of Science and Industry. This month, I will delve into the history of the fieldhouse, an early 20th century building type that was invented in Chicago and influenced the development of parks throughout America.

World’s Columbian Exposition Court of Honor Looking West, 1893. Chicago Public Library, Special Collections, WCE CDA 2_5. Photograph by C.D. Arnold.

Chicago’s South Park Commission (SPC) developed the nation’s earliest fieldhouses as part of an innovative movement to provide recreational facilities and social services to overcrowded tenement neighborhoods on the city’s South Side. Daniel H. Burnham, Chief of Construction for the Columbian Exposition, was the lead architect for these pioneering park buildings. In 1905, as the first ten fieldhouse complexes were nearing completion, Henry Foreman, the SPC Board President, published an article entitled “Chicago’s New Park Service” in Century Magazine. He explained that “The fieldhouses reflect in miniature the architectural beauty of the World’s Fair buildings,” noting “the designers of the White City—D.H. Burnham & Co.—drew their plans.”

Representing, in small scale, the Exposition’s Court of Honor, many of the fieldhouses (as shown here at Davis Square) were designed as an architectural complex surrounding an outdoor swimming pool. Photo courtesy of Woodhouse Tinucci Architects.

During the late 19th century, representatives of the SPC had become deeply concerned that their existing park system could no longer serve the needs of all South Siders. As Chicago experienced tremendous industrial growth, the population was surging. When the SPC had first formed, the city had a population of 300,000. By 1900, that figure had increased to 1.7 million, and nearly 750,000 residents were living at least a mile away from any park. The commissioners were deeply concerned about the neighborhoods within their jurisdiction that had little access to green spaces and social services.

Women and children in the street, ca. 1902. Chicago History Museum DN-0000522.

According to Foreman, when they surveyed conditions within their territory , the commissioners found “hordes of dirty and poorly clothed children swarming in the public ways,” mothers “with no green spot” nearby “to refresh them or their little ones,” and “men weary from hard labor, with few places for beneficial recreation to break the monotony of their lives.” Working in close collaboration with J. Frank Foster, Superintendent of the SPC, the commissioners decided that they must develop a new type of park with year-round facilities that would respond to the needs of those living in the congested South Side tenement neighborhoods.

McKinley Park swimming lagoon, ca. 1905. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

The commissioners acquired a 34-acre site near the stock yards to create McKinley Park in 1901. This represented the first new SPC park to be created in 30 years. Although McKinley Park did not initially include a fieldhouse, it had ballfields, a playground, a swimming lagoon, and a building with changing and locker rooms. The experimental park proved to be an immediate success. This prompted the commissioners to build a more ambitious system of neighborhood parks that would provide open space, recreational programs, and social services throughout the South Side.

Davis Square Vicinity Map, 1910. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Drawings.

In 1903, the South Park Commissioners received the legislative approval to establish new parks and issue bonds to cover the costs of the extensive construction program. Making a careful study of the neighborhoods they served, the commissioners sought to create at least one park within walking distance of nearly every home within their district. They planned a system of 14 new parks, ranging from seven to 322 acres in size. The SPC hired the Olmsted Brothers landscape architects and D.H. Burnham & Company architects to design the neighborhood parks.

Public bathing facilities in Davis Square Park, ca. 1905. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

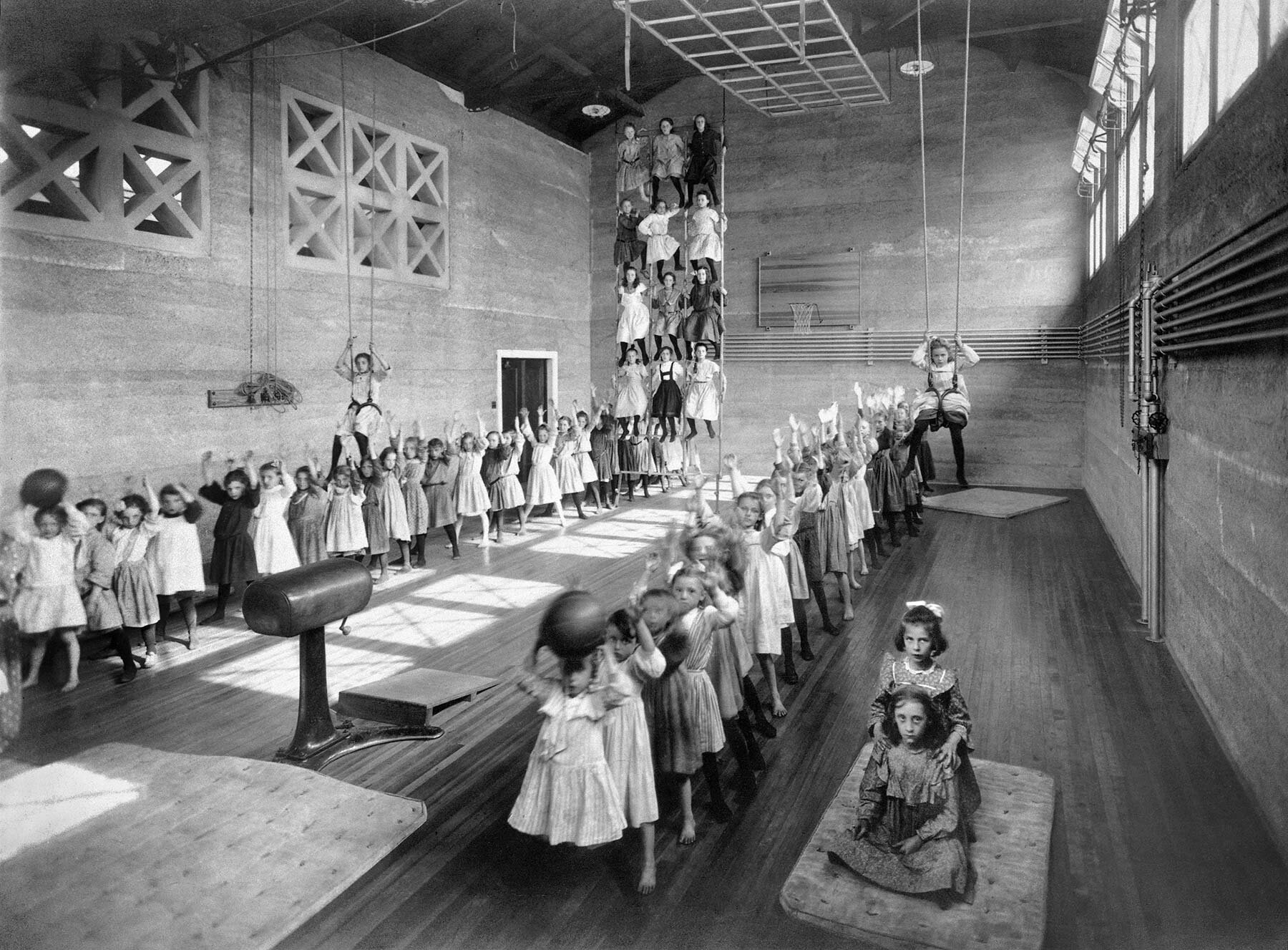

Despite the variance in acreage, each of the new parks provided such outdoor amenities as ballfields, swimming and wading pools, playgrounds, and running tracks and an entirely new type of building that had never existed before, the fieldhouse. Inspired by Chicago’s settlement houses, these buildings were intended as vehicles of social reform. Allowing for the year-round use of Chicago parks for the first time, the structures included separate gymnasiums for boys and girls; showers and lockers which provided public bathing to many Chicagoans who lacked running water; early branches of the Chicago Public Library; auditoriums, clubrooms, and classrooms; and lunchrooms, which offered hot meals at low price.

A pass the ball relay in the girls gymnasium of Mark White Square, 1905. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs.

Hamilton Park Fieldhouse. Photo by Michael Lange, Chicago Park District.

Soon after Daniel H. Burnham entered into contracts to design the SPC fieldhouses, he hired a talented young architect, Edward H. Bennett (1874-1954), specifically to assist him on this large-scale project. Having studied at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Bennett shared Burnham’s passion for Classicism. Like the park landscapes, the fieldhouse complexes all had similar characteristics, but the plans and details were individualized to make each structure unique. Nearly all of these classically designed complexes were built of exposed aggregate concrete, a relatively inexpensive material from which buildings could be constructed quickly and ornamentation could be molded directly onto facades.

By the late fall of 1905, ten of the new parks had been completed and opened to the public. Featuring the nation’s first fieldhouses, these were: Armour, Cornell, Mark White (now McGuane), Russell, and Davis squares, and Bessemer, Palmer, Ogden, Sherman, and Hamilton parks. One year later, the fieldhouses in these parks had been utilized more than five million times by South Siders.

Boys in line for bathing suits in Davis Square Fieldhouse, ca. 1905. Chicago Park District Records: Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Photographs

In 1907, Chicago was selected to host a national park and playground conference. President Theodore Roosevelt suggested that municipalities throughout the country should send representatives to this conference so that they could see the “magnificent system that Chicago has erected in its South Park section—one of the most notable civic achievements of any American city.”

Sherman Park Fieldhouse. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia.

The SPC’s revolutionary fieldhouses soon influenced the development of other parks throughout Chicago and in cities across the nation. Today the Chicago Park District (CPD) owns and operates more than 240 fieldhouses, and the district continues to develop new facilities. My former colleagues at the CPD realize that these buildings are truly special places. In fact, Doreen O’Donnell, the CPD’s Deputy Director of Planning and Development, recently created this video showcasing Chicago’s park fieldhouses.