Aerial view of Jackson Park’s Wooded Island and Surrounding Landscape, ca. 1935. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

Jane’s Walk Tour of Humboldt Park, 2013.

During the first weekend in May every year, people in cities - worldwide celebrate the birthday of author and “urban planning guru” Jane Jacobs (1916 – 2006). They don’t do so by attending parties, but rather, by taking free tours called Jane’s Walks. Jacobs was a prolific writer whose 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, challenged the urban renewal movement. Suggesting that cities become safer when there are many “eyes on the street,” she described interactions in vibrant public spaces as the “ballet of the good city sidewalk.” I think that analogy fits parks as well, and so I began leading Jane’s Walks in 2013, when Martha Frish, local preservationist, planner, and tour aficionado, brought the program to Chicago.

I’ve always wanted to explore Chicago’s parks at night, but have rarely had the opportunity to do so. That’s why I’m very excited to announce that, this year, as part of Jane’s Walks Chicago, I’ve organized a Flashlight Tour of Jackson Park. To allow for more participants and make this event even more special, I’ve invited three very knowledgeable colleagues to assist: Tim Samuelson, Chicago’s official cultural historian; Ray Johnson, founder of Friends of the White City; and Lauren Umek, a Chicago Park District ecologist who has been guiding the current restoration of Jackson Park. We’ll be quite a team! I hope you’ll join us on May 6, 9:00-10:30 p.m. Please RSVP online.

If you’ve visited Jackson Park recently, you know that it is undergoing a multi-million dollar landscape restoration project. Although the construction fencing may seem like an annoyance, this is an exciting initiative, as it is Jackson Park’s first extensive landscape improvement since the 1930s. There have been good smaller projects over the past 25 years to restore and manage various areas, but the park’s nearly 550 acres had fallen into decline— invasive plants were taking over and the entire habitat was suffering. With support from the US Army Corps of Engineers and Project 120, the ambitious “bio-cultural restoration,” project seeks to integrate ecosystem restoration with landscape preservation goals. An impressive team from the Chicago Park District, Corps of Engineers, and Heritage Landscapes-- a firm specializing in Olmsted landscapes-- worked together to create complex and highly-detailed plans for the project. These plans include over 600,000 new native plants, representing more than 300 different species of trees, shrubs, vines, grasses, flowers, and aquatic plants. The project also involves installing nearly 8,000 linear feet of new crushed gravel paths and overlooks to provide better access to the park’s landscape.

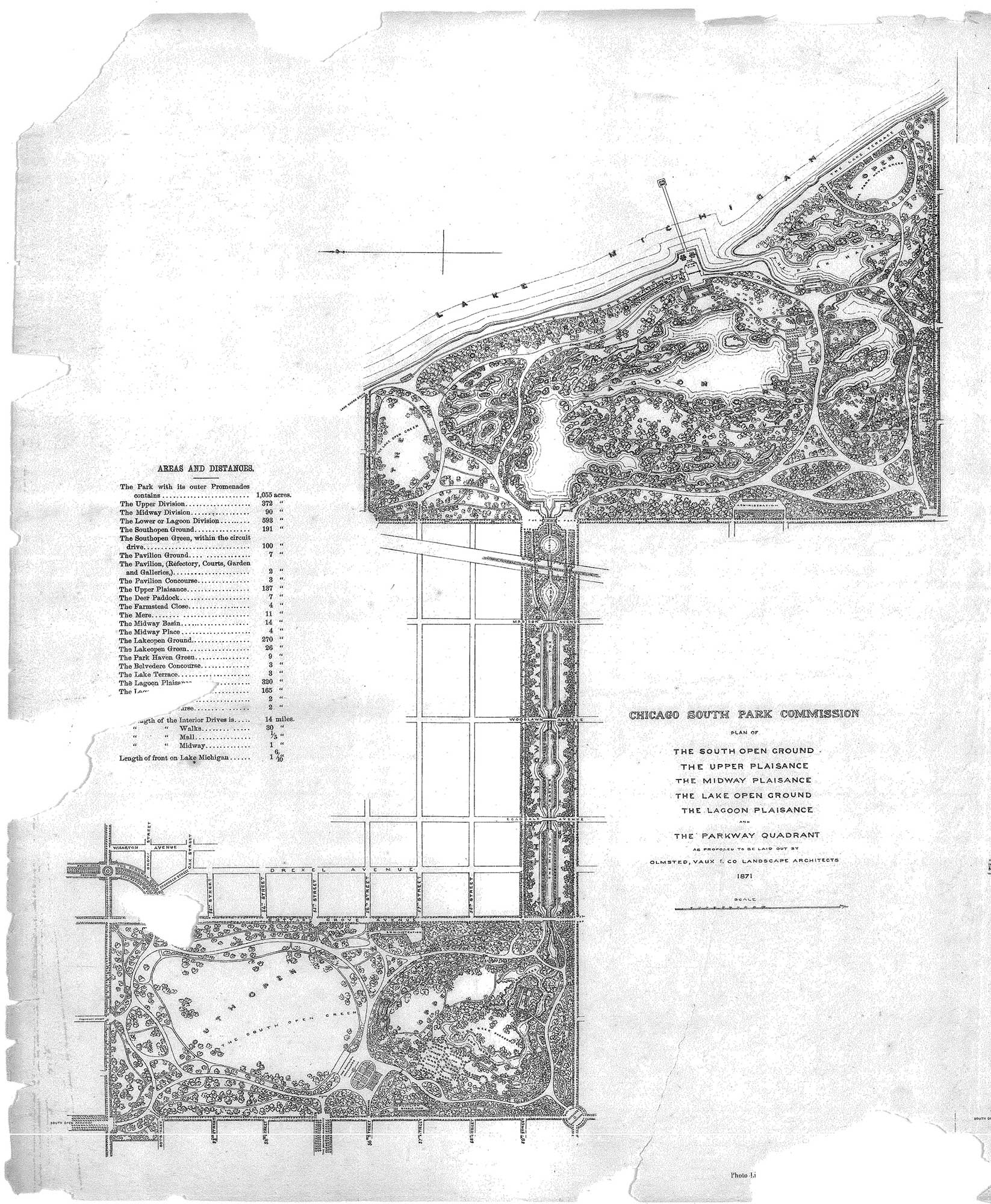

Now that you know about the construction in the park, I’d like to share more about why this place is so important and beautiful. Frederick Law Olmsted (1822- 1903), widely recognized as “Father of American Landscape Architecture,” designed Jackson and Washington Parks and the Midway Plaisance as a large unified landscape known originally as South Park. He laid out such seminal landscapes as New York’s Central Park; Boston’s Emerald Necklace; the National Capitol Grounds in Washington D.C.; Stanford University’s campus; and nearby Riverside, IL. In addition, he led movements to save two of the nation’s most significant natural areas, Niagara Falls and the Yosemite Valley.

Jackson Park is especially significant because Olmsted produced full plans for the park on three separate occasions. With his first partner, English architect Calvert Vaux (1824- 1895), he created the original plan for South Park in 1871. When Olmsted first visited the south lakefront site, he didn’t consider it very promising. In fact, he wrote, “If a search had been made for the least parklike grounds within miles of the city, nothing better meeting that requirement would have been found” (Inland Architect, 22, no. 2, Sept. 1893” p. 19). However, he did appreciate its relationship with Lake Michigan; each of his plans took advantage of the site’s lake frontage.

Jackson Park Lagoon Looking East, July, 1891. Chicago Public Library, Special Collections, WCE CDA 1.1. Photograph by C.D. Arnold.

World’s Columbian Exposition Court of Honor Looking West, 1893. Chicago Public Library, Special Collections, WCE CDA 2_5. Photograph by C.D. Arnold.

The original plan sought to transform the marshy “Eastern Division” of into a series of interconnected waterways that would wind along a large lushly planted peninsula and scattered small islands. Only minor improvements were made, however. In 1883, the Eastern Division was officially named Jackson Park. The park’s selection as the site for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition spurred Olmsted’s second plan. This time, Olmsted collaborated with a younger landscape designer, Henry Codman, and Chicago architects, Daniel H. Burnham and John Wellborn Root, to lay out the fairgrounds. In an 1892 report to Thomas W. Palmer, President of the World’s Columbian Commission, the designers described a vast interlinking waterway system featuring “a great architectural court with a body of water,” that would provide “water, as well as land frontage” to “the principal Exposition buildings.” The report also suggested that in “the middle of this lagoon system there should be an island, about fifteen acres in area.” With clusters of large trees and “free of conspicuous buildings,” the space was meant to be “generally secluded,” and “naturally sylvan.” By re-shaping what had been shown as the original plan’s peninsula into a large island, the designers envisioned the landform that would become Jackson Park’s famous Wooded Island.

Despite efforts to keep Wooded Island free of buildings, many requests came in for pavilions and other amenities there. According to Olmsted’s Inland Architect article, the designers determined that, of all the suggestions, “the least intrusive and disquieting result” came from Japanese government’s proposed pavilion; as well as various floral displays sponsored in conjunction with nearby Horticultural Hall. To get a better sense of Wooded Island then, check out simulations created by Lisa Snyder of the UCLA Urban Simulation Team.

Ho-o-den Pavilion and Japanese Garden in Jackson Park, ca. 1935. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

The Japanese Pavilion, known as the Ho-o-den, remained in the park until it was destroyed by fire in 1946. Today a new sculpture by Yoko Ono sits on the Ho-o-den site. After the fair, Olmsted created his third plan to transform the fairgrounds back to parkland. This Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot Plan of 1895-97 served as the template for the current restoration work. You’ll learn more about this if you can join us for the Jane’s Walk Flashlight Tour on May 6th!