Swedish immigrants founded Edgewater’s Ebenezer Lutheran Church and hired Andrew E. Norman to design their limestone-fronted edifice. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

When researching Chicago history, I’m continually astounded by the vast number of architects who created important buildings, but are now largely forgotten. By documenting the contributions of talented, lesser-known architects, we can learn more about the city, while also trying to save these unsung heroes’ works from the wrecking ball. This fall I will lead a four-part Chicago Architecture Center series entitled “Beyond the Big Names: Lesser Known Architects in Chicago History” from October 22 through November 12, 2019. (Registration at architecture.org.) Over the next few months, I plan to write several blogs on this theme, and I’m starting here with Swedish-born architects.

L.G. Hallberg designed the Mason Brayman Starring mansion at 1254 N. Lake Shore Drive. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

An amazingly large number of talented late-19th-century Swedish immigrant architects collectively produced thousands of fine buildings throughout Chicago and its suburbs. One of the earliest was Lawrence Gustav Hallberg (1844-1915). Although many architectural enthusiasts may not recognize his name, Hallberg designed some very prominent Chicago buildings.

With red face brick and a mansard roof, even the rear façade of 1254 N. Lake Shore Drive is impressive. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Hallberg, who earned a civil engineering degree from the Chalmers Polytechnic Institute in Gottenberg and studied architecture at the Fine Arts Academy in Stockholm, began his career before emigrating. He helped rebuild the Swedish city of Gefle after its destruction by a devastating fire. Hallberg was practicing in London when he learned about the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and opportunities to rebuild drew him here. He soon received high-profile commissions. For example, he designed a Romanesque Revival style mansion at 1254 N. Lake Shore Drive for attorney and railroad executive Mason Brayman Starring.

L.G. Hallberg, Jr., produced this luxury apartment building at 3314 N. Lake Shore for businessman Charles B. Smith. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

In 1913, Hallberg brought his son into partnership. Like his father, Lawrence Gustav Hallberg, Jr. (1887-1971) had been academically trained—he received a degree in architecture from Cornell University. The two practiced together for only two years before Hallberg, Sr., passed away. Following in his father’s footsteps, Hallberg, Jr., created a number of significant local buildings. A Beaux Arts style luxury apartment building at 3314 N. Lake Shore Drive is among them.

Andrew Sandegren, The Swedish Element in Illinois by Ernest W. Olson, 1917.

Another Swede who was responsible for many impressive residential structures was Andrew Sandegren (1867-1924). After studying at the Carolinian Cathedral School at Lund, he immigrated to America at the age of 21. After briefly working in Chicago, Sandegren moved to the East Coast. He worked under a number of architects before establishing his own Chicago practice in 1902. Although he initially created plans for a broad range of building types, Sandegren quickly grew to specialize in apartment buildings. He produced hundreds of multi-family structures throughout the city and nearby communities. Architectural historian Carroll William Westfall credits Sandegren with creating what would become a ubiquitous part of Chicago’s apartment structures: the enclosed sun porch or solarium. This feature can be seen in many of Sandegren’s buildings, including his flats at 813-815 and 819 W. Buena Avenue, listed in the Buena Park National Register (NRHP) Historic District.

Sandegren-designed apartments at 813-819 W. Buena Avenue. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

John A. Nyden, The Swedish Element in Illinois by Ernest W. Olson, 1917.

Perhaps one of the most prolific of Chicago’s Swedish architects was John Augustus Nyden (1878-1932). Born John Augustus Carlsson in Sweden, Nyden spent his childhood helping his tradesman father and learning to read architectural plans. At the age of 17, he changed his name and immigrated to Chicago. He joined Lakeview’s Swedish Evangelical Lutheran Mission Church and found work as a bricklayer while attending evening classes to learn English. He studied at Valparaiso University for several terms, and then worked as a draftsman in New York for one year. Nyden returned to Chicago, and became chief draftsman for the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company. Completing his architectural studies at the Art Institute and the University of Illinois in Urbana, he opened his own office in Chicago in 1907.

Victory Monument at 3500 S. Martin Luther King Drive. Photo courtesy of Wikicommons.

During WWI, Nyden served in the military, supervising the development of 42 hospitals throughout the nation. Later, he collaborated with sculptor Leonard Crunelle on the Victory Monument, an evocative memorial to an African-American WWI regiment, located in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood.

Nyden became well-known creating beautiful single-family homes and apartment buildings. Among his residential projects are a courtyard building at 544-550 Sheridan Road in Evanston, a double courtyard structure at 534-552 W. Brompton Avenue, and a luxury apartment tower at 257 E. Delaware Place. Nyden lived in Chicago’s Edgewater neighborhood before moving to Evanston in 1921. Sadly, the Classical Revival style home he designed for his own family in Evanston was recently demolished.

Nyden’s courtyard building at 544-550 Sheridan Road in Evanston. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Nyden was especially devoted to Swedish organizations. He designed the Edgewater Swedish Covenant Church at N. Glenwood and W. Bryn Mawr Avenues, as well as several major buildings for North Park Theological Seminary. (He eventually become a trustee for this Swedish-American institution.) In 1926, Nyden was chosen as the architect for the American Swedish Historical Museum (originally the John Morton Memorial Museum) in Philadelphia, a project that would become the capstone of his career despite the fact that he died several years before the museum’s completion.

Nyden designed the Swedish Covenant Church in Edgewater. Photo by Jeff Reuben.

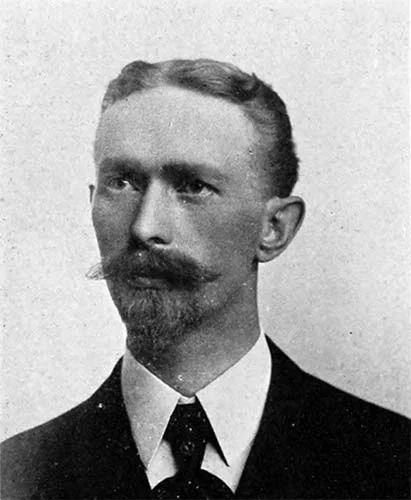

Andrew E. Norman, ca. 1885. Photograph courtesy of Chris Kale Corcoran.

Andrew E. Norman (1860-1934) was another extremely productive Swedish-born Chicago architect. The son of a forester, Norman apprenticed under a patternmaker at the Finnshytlan Mechanical works at the age of 16. Arriving in America in 1880, he spent about six months as a cabinetmaker in Brooklyn before relocating to Michigan. There, Norman married a fellow Swede and became the foreman in a furniture factory. An avid ice skater, he was also an accomplished woodcarver who often won prizes in competitions. In 1887, the Normans moved to Chicago, where he established himself first as a contractor and then as an architect. He lived and worked in Edgewater for the rest of his life.

LeRoy Blommaert of the Edgewater Historical Society (EHS) has done extensive research on Norman’s work in the neighborhood. Blommaert had long suspected that Andrew Norman was responsible for numerous houses on the 1400 and 1500 blocks of W. Hood Avenue. As explained in an EHS web posting, Norman’s great-granddaughter, Chris Kale Corcoran, unearthed a 1904 article in the weekly Swedish-language newspaper Svenska Nyheter confirming that her ancestor designed the Hood Avenue houses for Weber-Kranz developers. Blommaert believes Norman also produced other similar houses on nearby blocks for the same firm.

Left: Rozek House with its original front soon after its 1908 completion. Right: Rozek House with Norman’s front addition. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

I first learned about Norman when researching my own home in Edgewater, the Theodore Rozek House. Although the Four Square was designed by Clarence Hatzfeld in 1908, the Rozeks retained Norman to create a new front addition with a half-wraparound porch in the mid-1920s. (I was fortunate to inherit the original blueprints for both the house and the addition.)

Norman designed this building at 6318-6320 N. Clark St. in 1909 to house a saloon with flats above. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Norman produced a broad array of building types in Edgewater. His corner mixed-use structure at 6318-6320 N. Clark Street began as a saloon around 1910, later became a branch Sears Roebuck & Co. store, and is now a pool hall. Norman’s most iconic structure in the neighborhood is the Ebenezer Lutheran Church at 1650 W. Foster Avenue, a fine limestone edifice that features the architect’s own interior wood carvings.

Ebenezer Swedish Lutheran Church during construction, 1907. Photograph courtesy of Chris Kale Corcoran.

Another Swedish architect who had strong ties with Chicago’s North Side was Charles A. Strandel (1866-1937). After receiving a degree from a technical college in Karlstad, Sweden, Strandel immigrated to Grand Rapids Michigan in 1887. He soon relocated to Chicago, finding work under various local architects. He opened his own office in Lakeview around 1893. Strandel quickly became busy, and by 1905, he moved his practice downtown to the Tacoma Building. Although he largely specialized in residential buildings on the North Side, Strandel also produced mixed-use, commercial, and manufacturing structures throughout the city and in nearby suburbs. His work includes a corner mixed-use structure at 5357 N. Ashland Avenue in the NRHP Andersonville Commercial Historic District; a six-flat at 2407-2409 N. Kedzie Avenue in the NRHP Logan Square Boulevards Historic District; and sister three-flats at 639 and 645 W. Sheridan Road.

Strandel’s store and flats at 5357 N. Ashland. Photograph by Julia Bachrach.

Today, many Chicagoans know that the Edgewater’s Andersonville neighborhood was a Swedish enclave. However, few realize that in the past, many Swedes lived and worked on the South Side. Among them was architect Anders Gustaf Lund (1857-1934). Born on a farm in central Sweden, he showed an early talent for drawing. Lund’s uncle, the engineer for the city of Abo, encouraged him. Lund studied architecture at the Technical Institute of Stockholm and immigrated to Chicago in 1882. He had a three-year apprenticeship under a construction carpenter, P. A. Westberg of Englewood. Lund then worked for various local architects and opened his own office in Englewood in 1892. He received commissions from clients throughout the South Side. Among his early buildings is the Chicago Bicycle Club at 718 W. Garfield Boulevard. His enormous body of residential work includes sister courtyard structures at 6700-6710 and 6701-6711 S. Merrill Avenue, both completed in 1922.

Lund-designed courtyard building at 6700-6710 S. Merrill Avenue. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

I think I’ve only skimmed the surface of the contributions to Chicago by Swedish immigrant architects. However, I hope I’ve given you a glimpse into this immense theme. And to think, this is only one of many threads I will be covering in “Beyond the Big Names”!