Official World’s Fair Pictures Souvenir Book, 1933.

May 27th will mark the 85th anniversary of the opening of Chicago’s Second World’s Fair, A Century of Progress International Exposition. The fair celebrated the centennial of Chicago and the city’s many achievements during its first 100 years.

A team of the nation’s leading architects designed the fair’s gleaming campus of modern buildings along Northerly Island and Burnham Park. Visitors were amazed by exhibits, attractions, and innovations such as a voice-controlled robot, baby incubators, air-conditioning, and an automobile production line. Fairgoers were also entertained by rides, pageants, special events, and side-shows. By the end of its second season, approximately 48 million visitors from all over the world had attended A Century of Progress. The fair took place during the dark days of the Great Depression and it gave visitors a bright sense of optimism about the future.

This view shows crowds at the Enchanted Island area of A Century of Progress, looking south towards the Horticulture Building. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

My grandmother, Piri Klein Neumann, left, and her aunt Sharika Farkas, right, had their photograph taken in a photo booth at A Century of Progress, 1934.

The fair played an extremely important role in my own family’s history. My Hungarian Jewish grandmother, Pirosca “Piri” Klein, had grown up in village in Transylvania. Wanting a more adventurous life, she moved to Paris around 1930. A few years later, she was eager to come to America. It’s not that she could foresee how Jews would be treated in France by end of the decade, but Piri didn’t have proper immigration documents to stay in Paris. She had an aunt named Sharika who had immigrated to Chicago. By the fall of 1933, organizers of A Century of Progress had decided to extend the fair for another season. Because of this, visitors’ visas were readily available, and soon my grandmother arrived in Chicago and began living near Humboldt Park with Sharika and her family. During one of several times that Grandma Piri and Aunt Sharika visited A Century of Progress, they had their photograph taken in an early photo booth that was part of a fair display.

Aunt Sharika, left, and Grandma Piri, right, 1996.

Before long, Piri met and married my grandfather, Armin Neumann, a Hungarian immigrant chandelier-maker. My grandmother helped my grandfather establish a successful business called New Metal Crafts. They had a family and a happy life in Chicago. They were lucky to have left Europe before the Nazis invaded, but many of their relatives were not as fortunate. After the war, my grandparents helped some family members who survived the Holocaust come to America. I think when my grandmother (who passed away in 1998) looked back at her early life as an American, A Century of Progress represented the bright future and good fortune she would have as a Chicagoan and as an American Jew.

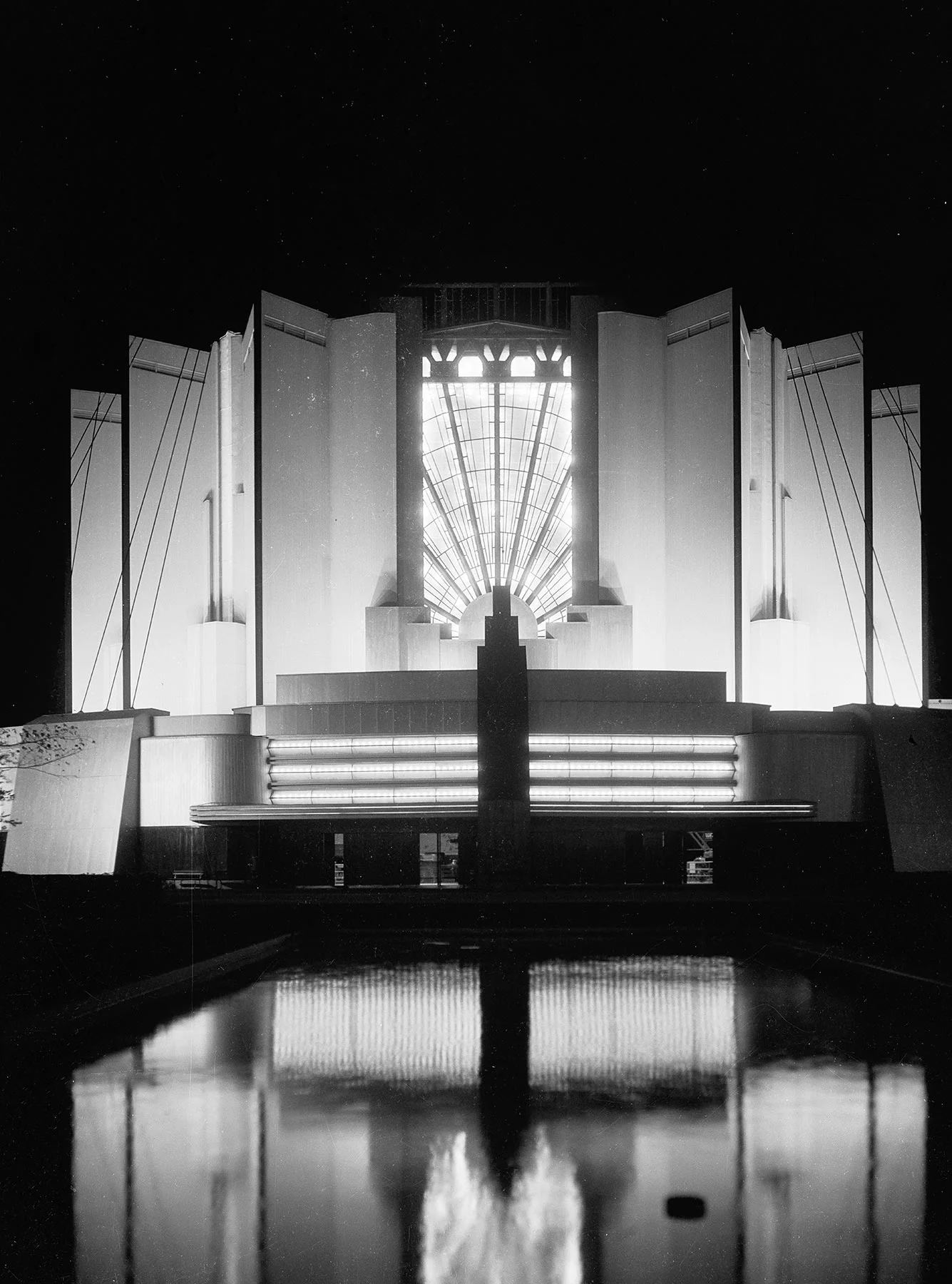

Travel and Transport Building at night with lighting effects. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

While this story is personal to my family, the connotation of A Century of Progress as “The Bright City” applies more generally. Because Chicago’s first World’s Fair—the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition—was composed almost entirely of enormous white Beaux Arts style buildings, it was nicknamed “The White City.” In contrast, the 1933-34 Second World’s Fair’s campus of Modern buildings in bold hues might be considered “The Bright City.” Today, when we see the many black and white photographs of the fair, it’s hard to imagine that large blocks of intense color provided the unifying theme for the fairgrounds. With nighttime photos, it’s obvious that the “Bright City” theme encompassed new lighting methods and technologies, such as neon.

Travel and Transport Building, left, and Hall of Science, right. American Asphalt Paint company, ca. 1932.

The south lakefront fairgrounds, an asymmetrical site created from landfill, posed challenges to the designers. Lenox Lohr, General Manager for A Century of Progress considered the site “strangely structured” and he had concerns about its “informally arranged architectural plan.” Lohr explained the color “was the common denominator” which provided the unifying theme. He suggested that a “carnival of color, brilliant and startling, was the flame” that “blended” the disparate parts of the fairgrounds into a cohesive setting, creating the “fiesta spirit so essential to a world’s fair.”

Joseph Urban, ca. 1915, Wikimedia Commons.

The fair’s “riot of color” was made possible by Joseph Urban (1872- 1933), an architect and theatrical designer. Born in Austria, Urban was the son of a prominent educator. When Urban decided to study architecture instead of the law, his father disowned him. The president of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and Polytechnic in Vienna recognized Urban’s extraordinary talent and gave him a scholarship. After completing his studies, Urban received a commission to decorate the Palace for the Khedive of Egypt in Cairo. He went on to design castles and other monumental buildings for European noblemen, as well as a “Czar’s Bridge” in Russia. Urban emigrated in 1911 when he accepted the position of art director for the Boston Opera Company. A few years later, he moved to New York and served as theatrical designer for the Metropolitan Opera and the Ziegfeld Follies.

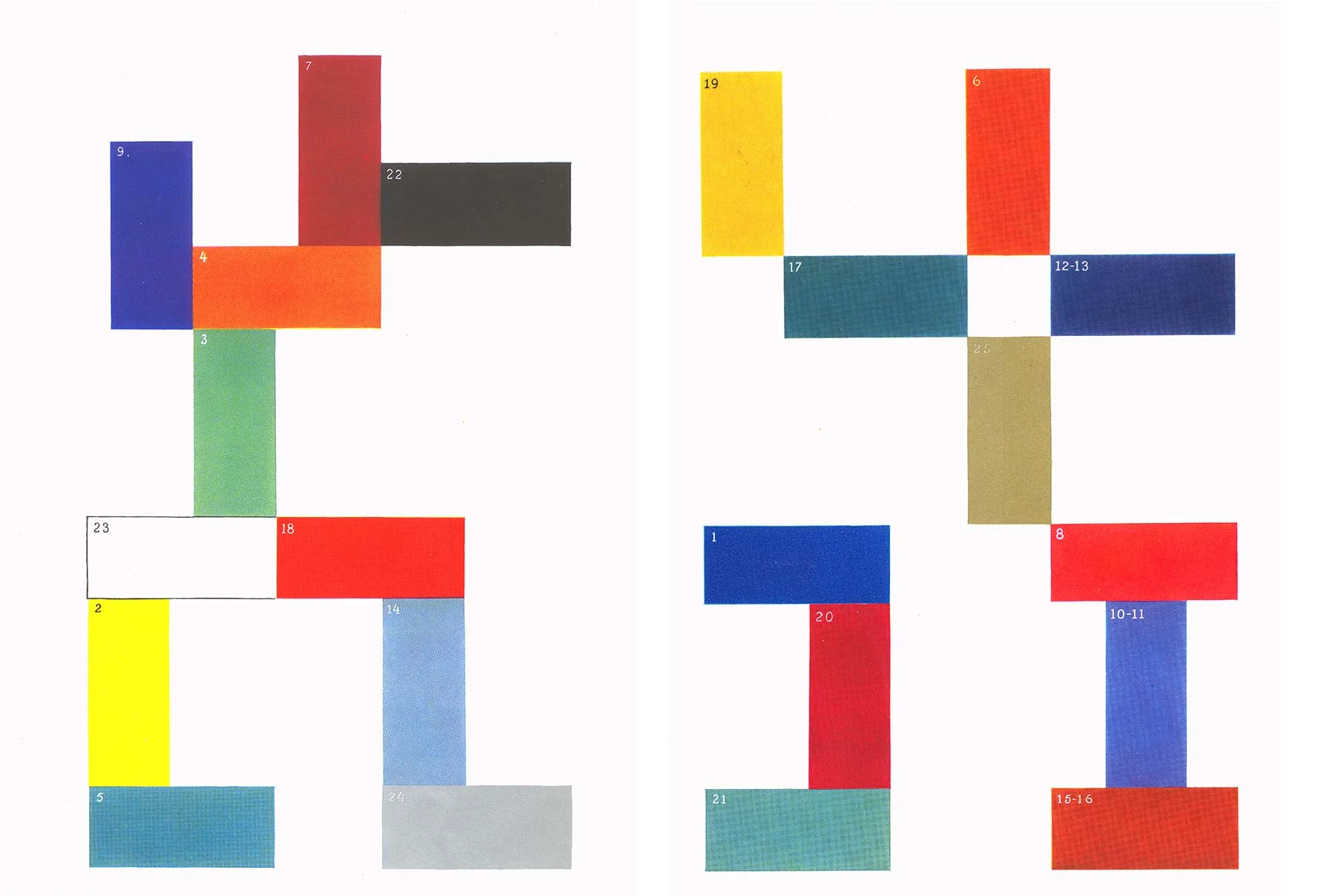

Joseph Urban’s original 1933 Color Charts. Courtesy of the Museum of Science and Industry.

As colorist for A Century of Progress, Urban developed a palette of 23 colors for the fairgrounds in 1933, including white; sulphur yellow; chrome yellow; light orange; dull Persian orange; two shades of vermillion; tomato bisque pink; and blues and greens ranging from emerald and peacock green to ultramarine and turquoise blue. He worked with the American Asphalt Paint Company to develop the custom colors. Providing the paint for over 10 million square feet of architectural surfaces, the company estimated that the job resulted in the largest single paint contract ever awarded. (In 1934, the paint palette was reduced to only ten colors.) According to Shepherd Volgensang, a member of the exposition staff, Urban’s underlying plans considered not just aesthetics but also “the moving of crowds.” Volgensang explained that the “huge buildings were the background for movement,” and that Urban “tried to get life, warmth, texture, and motion, into his color scheme.”

Morning glory fountain in the Electrical Court. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

Urban’s scope of work extended beyond selecting the paint for the buildings—his color scheme permeated all decorative effects on the grounds. He worked closely with William D’Arcy Ryan, the chief of illumination for the fair. Innovative lighting effects included outlining individual buildings, illuminating water, and using neon and other newly-developed technologies. A fountain located in the center of the Electrical Court emulated a giant morning glory, with a massive hammered-copper canopy representing the flower. At the center of the pool was a stepped basin with vertical streams emanating from jets at all four levels. Each band was illuminated by a different colored light-- red at the lower level, then yellow, green next, and blue at the top. The lights reflected by the copper canopy cast bright spectacles of color across the court.

Avenue of Flags. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

One of Urban’s most beloved “spectacles” was the Avenue of Flags. Located along Leif Ericson Drive, east of Soldier Field and south of the Shedd Aquarium, the long row of flags rose to a height of 85 feet. In 1933, the massive flags were red, each with a narrow yellow stripe. In 1934, they were changed to a soft turquoise color.

Sadly, Joseph Urban became ill during the planning of A Century of Progress. Because of his health, he did much of his work on the fair from New York. By the time the fair opened on May 27, 1933, he was in the hospital. Joseph Urban died on July 10, 1933, without ever seeing A Century of Progress, one of his great achievements.

If you’re now thinking, “I wish I could see what it really looked like,” you’re in luck. A Technicolor short film about the fair was discovered in the last couple of years.

In this family photograph from my wedding, my grandmother, Piri Neumann, is seated in the front, 1996.

Ten years ago, as the 75th anniversary of A Century of Progress approached, I had the pleasure of interviewing several Chicagoans who attended the fair. You can view the memories of Sam Guard and Peggy Carr. Unfortunately, my grandmother had already passed away at that time. I wish I would have taken the opportunity to ask her more specifically about her experiences at the fair, as I know A Century of Progress – “The Bright City” — meant so much to her.