Charitas in its newest location in Lincoln Park. Photo courtesy of Steven Casteel.

Talented Sculptress Dies,” Decatur Review, September 5, 1927, p. 12. (Getty Images mistakenly identifies Ida McClelland as an African-American artist. The mislabeled photo depicts Fanny Stout, not Ida McClelland Stout.)

Over the past couple years, there has been growing national awareness of the dearth of public artworks that pay homage to women in American history. While Chicago has only a small collection of monuments to significant women, many allegorical sculptures portraying female figures can be found throughout the city. It seems somewhat ironic that Charitas—a wonderful allegorical monument installed in Lincoln Park and moved around many times—was produced by a woman who has largely been forgotten. So, I’d like to share with you the story of the artwork and its sculptor, Ida McClelland Stout.

Born in Ohio to a family of Scottish and English heritage, Ida McClelland Stout (1881- 1927) grew up in Decatur, Illinois. Sometime around 1910, she moved to Chicago with her older sister Lillian. Both sisters were then in their mid-twenties. They lived on the North Side and worked together at a music school—Lillian as a music teacher and Ida as a secretary. In the late fall of 1911, the two travelled to Germany so that Lillian could study music. During the year or so that the Stout sisters lived in Berlin, Ida spent her time learning the craft of book-binding. According to the Decatur Review, while living abroad, Ida consulted a “noted German sculptor,” Herre Enke, who “encouraged her to take up sculpture on her return from Europe.”

“Certificate of Registration of American Citizen” for Ida McClelland Stout, December 6, 1911.

Soon after arriving back in America from Germany in 1913, Ida M. Stout entered the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She was very serious about her studies. A fellow student, Miss Ruth Sherwood, later told the Chicago Tribune that “she was a tireless worker, and never hesitated to devote holidays and evenings to her work, which was also her greatest joy.” A couple of years after Ida began studying at the Art Institute, renowned Czech sculptor Albin Polasek was appointed as the head of the Department of Sculpture there. He became an inspiring mentor, and Ida excelled.

Ida McClelland Stout’s Sun Dial, The Garden Magazine, January, 1922.

Ida McClelland Stout was soon winning art competitions. These included the 1919 and 1920 John Quincy Adams Scholarship Prize, which provided funding to study in Europe. Although delayed by the aftermath of WWI, in 1921 she used the scholarship to study art in England, Italy, and Switzerland. After returning to Chicago, she won additional art competitions. These included a contest sponsored by the Woman’s National Farm and Garden Association, in which she received a $50 prize for a figurative sculpture that served as a sun dial. Stout’s Sun Dial was described as characterizing “dignity with an aspect of reassuring permanence.”

Ida McClelland Stout at work on Charitas, 1922. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum DN-0074540.

In 1922, Ida McClelland Stout won an extremely high-profile competition sponsored by the Chicago Daily News. Ida submitted a model of Charitas, a figurative sculpture of a woman with one child on her shoulder and another in the crook of her arm. Open only to students and alumni of the School of the Art Institute, this contest granted Ida a $1,000 prize and the opportunity to create a permanent sculptural fountain for the Daily News Fund Sanitarium for Sick Babies. The Lincoln Park facility (now Theater on the Lake) served as a day nursery that treated children with tuberculosis and other diseases while also providing wholesome meals, fresh milk, and health care to undernourished children throughout the city.

Charitas and circular fountain in its original location just west of the Daily News Sanitarium for Sick Babies. Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Chicago Park District Archives, Photos.

The jurors for the prestigious Daily News competition were Frank G. Logan, Vice-President of the Art Institute; Charles H. Wacker, a prominent businessman and leader of the Chicago Plan Commission; architect Irving K. Pond; and artists Lorado Taft and Emil Zettler. After the jury announced that Stout’s Charitas had been selected, the Chicago Daily News reported that the artwork represented a “conception of the idea and ideal of The Daily News Fresh-Air Sanitarium.” (Although the sculptor had intended for the monument’s 30-foot circular basin to serve as a wading pool, it is unclear whether the fountain was ever used in that way.)

Woman and children standing along the edge of the original circular fountain, looking at Charitas, 1925. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum, DN-0079249.

In 1927, while on another study scholarship trip in Europe, Ida contracted a type of malaria known as Roman Fever, and she died quite suddenly. Had she lived longer, Ida McClelland Stout might have been better remembered. Another factor contributing to her obscurity is that Charitas was out of public view—and sitting in storage—for many years. In fact, the monument stood in its original location for less than two decades. The Chicago Park District first hauled Charitas away from Lincoln Park in the late 1930s, when a major reconstruction of Lake Shore Drive not only led to removing the bronze figure and destroying its basin, but also to razing the entire front of the Dwight H. Perkins-designed Sanitarium building.

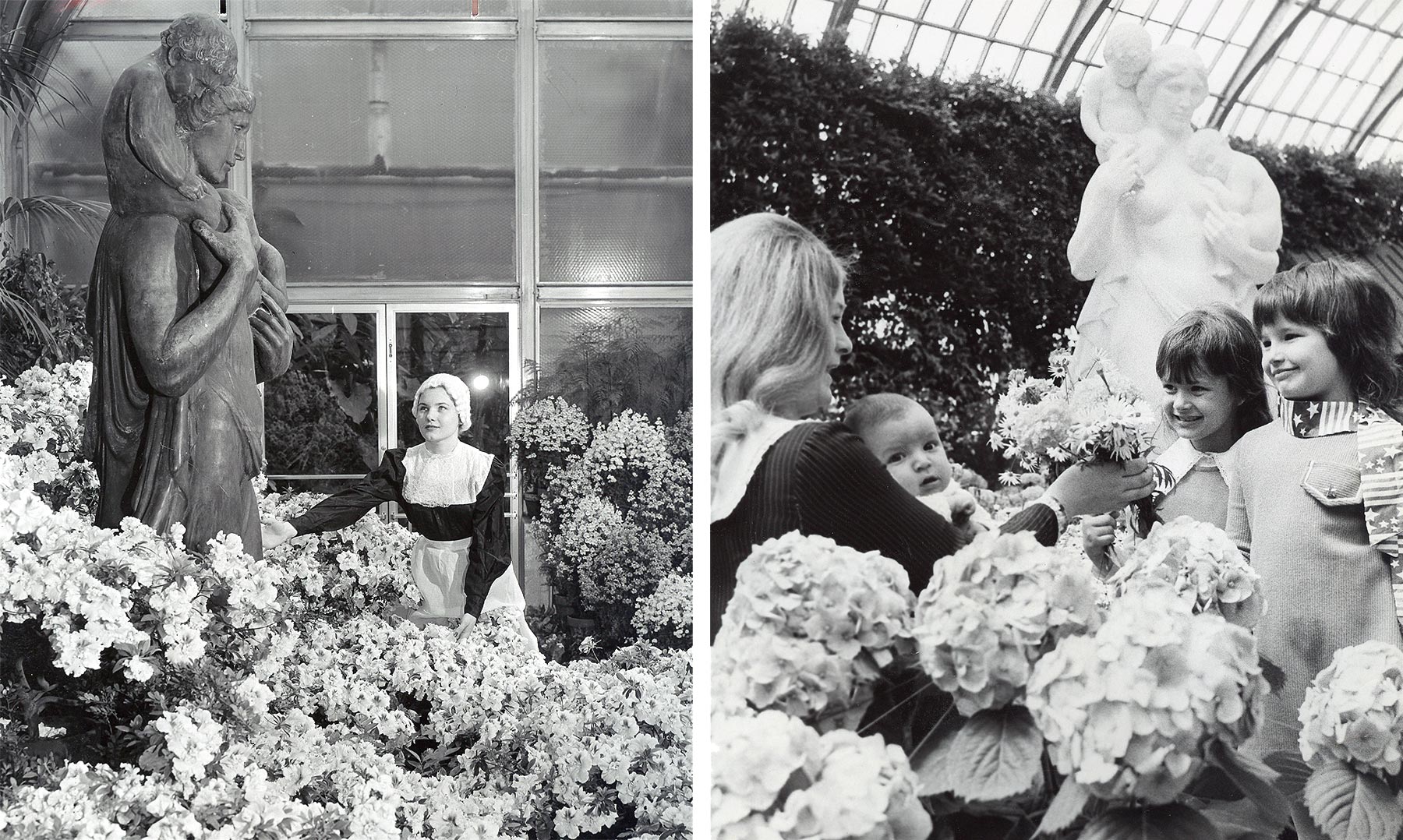

These photographs show Charitas in its second and third locations, in Lincoln Park in 1953 (L) and the Garfield Park Conservatory in the 1970s (R). Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Chicago Park District Archives, Photos.

Sir Georg Solti Bust in Lincoln Park, ca. 2000. Photo courtesy of Jyoti Srivastava.

After a long period in storage, Charitas was installed in the Lincoln Park Conservatory in the early 1950s. About 20 years later, the Chicago Park District moved the bronze sculpture to the Garfield Park Conservatory’s Show House. At that time, it was painted white, perhaps to make it look similar to Pastoral and Idyl, Lorado Taft’s marble figurative sculptures that stand in the conservatory’s Palm House. During this period, Charitas was separated from its original base. (In 1987, when a group of private donors commissioned a portrait bust of Sir Georg Solti for installation in Lincoln Park, Chicago Park District administrators allowed them to mount it on the Charitas base.)

Charitas remained in the Garfield Park Conservatory for about 30 years. During the late 1990s, professional conservator Andrzej Dajnowski removed the white paint and restored the sculpture back to its original warm brown patina. Over the next few years, renovations and improvements at the Garfield Park Conservatory led to the monument’s return to storage.

Charitas on the lawn adjacent to Theater on the Lake, 2016. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

During my long tenure at the Chicago Park District, I often advocated for reuniting Charitas with its original base and returning the artwork to Lincoln Park, somewhere near Theater on the Lake. Michael Fus, the Park District’s Preservation Architect, agreed and began to champion this cause. After the completion of a new landfill extension east of Fullerton Avenue, and under Michael’s direction, Charitas was reinstalled just south of Theater on the Lake in 2016.

Charitas at its existing location in Lincoln Park south of Theater on the Lake, 2018. Photo courtesy of Jeff Zoline.

But the saga of the sculpture didn’t end there. When Theater on the Lake underwent a recent $6 million renovation, the project included constructing a new terrace that required moving Charitas yet again. Michael Fus shepherded the relocation of the artwork. He selected a new site further south of Theater on the Lake, positioning the bronze woman and two children to face the building, in a manner similar to the monument’s original placement. Let’s hope that this will be the final home for Ida McClelland Stout’s wandering sculpture!