Paddle boats in Humboldt Park’s Lagoon. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

Recently, as part of a dinner cruise, I gave a presentation on a Lake Michigan yacht. Beforehand, while standing on the upper deck and gazing at the glimmering water and green parkland in the distance, I thought about the glorious boating tradition in our city. The Chicago Yacht Club’s Race to Mackinac has been an annual event since 1898. The Air and Water Show has been enjoyed annually for nearly 60 years, and will soon take place during the weekend of August 18 – 19.

“Miss Mermaid” Contestants at Chicago’s Air and Water Show, 1965. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

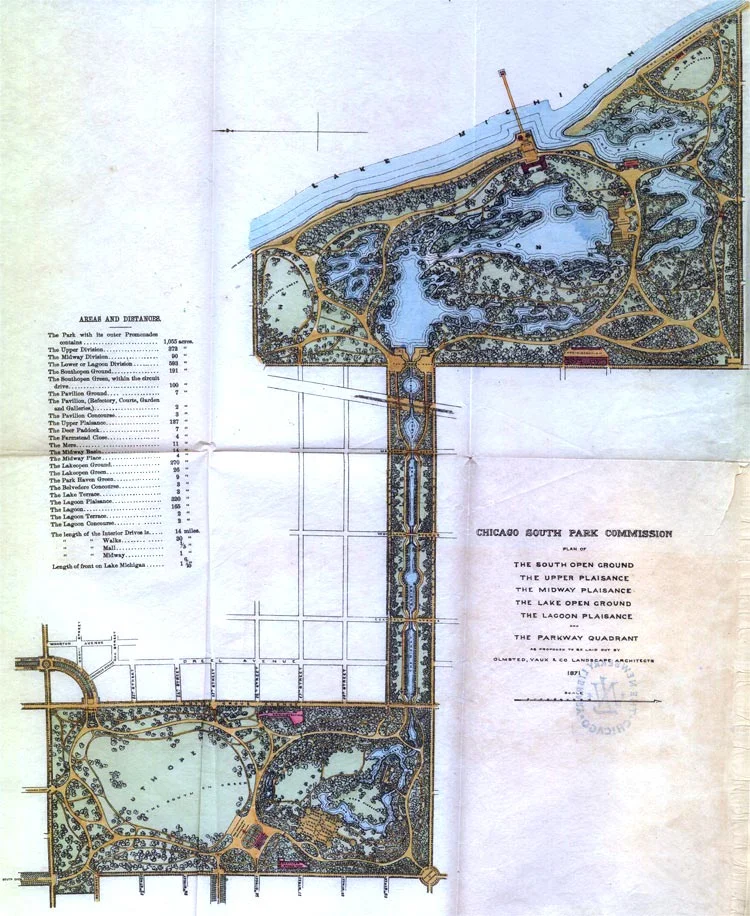

Plan of South Park (now Jackson and Washington Parks and Midway Plaisance), Olmsted & Vaux, 1871. Courtesy of Newberry Library.

The story of boating in Chicago is closely tied with park development. In 1870, when renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) and his then-partner, Calvert Vaux (1824-1895), began laying out Chicago’s South Park—a large green space that would become known as Jackson and Washington Parks and the Midway Plaisance—they clearly had boating in mind. Olmsted felt that Lake Michigan, the “one object of scenery near Chicago of special grandeur or sublimity,” could be connected with interior waterways, making the park ideal for boating. In their 1871 plan, Olmsted & Vaux envisioned Jackson Park’s lushly-edged lagoons adjoining a circular turning basin at the eastern end of the Midway Plaisance. Just to the west, they wanted a grand canal to extend through the center of the Midway Plaisance and flow into the Mere, Washington Park’s southern lagoon. Although the South Park Commissioners made several attempts to build the Midway canal, the linear waterway was never realized.

The city’s West Park Commissioners had also realized early on that they would have to build their parks in stages. Architect, engineer, and landscape designer William Le Baron Jenney (1832-1907) had created original plans for Humboldt, Garfield, and Douglas parks. Each plan featured a lagoon with boat landings. The commissioners initially improved a 40-acre portion of Garfield Park (originally called Central Park) and opened it to the public in 1874. Two years later, the commissioners placed six row boats in the park’s lagoon for public use. When, at the end of the season, more than 10,000 patrons had used the boats, they decided to add more the following year. By the early 1880s, row boats could be rented at all three parks.

Boaters near suspension bridge in Central (Garfield) Park, 1875. From Sixth Annual Report of West Chicago Park Commissioners.

Lincoln Park’s boating tradition began around the same time as in the South and West parks. Landscape gardener Swain Nelson (1828-1917) created the North Side park’s original 1865 plan, which featured a series of three artificial lakes joined by winding narrow streams with rustic bridges. In the early 1870s, the Lincoln Park commissioners began providing boats for rowing on the three connecting lakes. The Chicago Tribune reported on March 24, 1889 that the commissioners had made arrangements to lease paddle boats from the Western Bicycle Swan Boat Company. Each of these boats was operated by a “boy sitting inside a large white iron swan” peddling and steering at the back, with four settees for passengers in front of him.

Left: Swan boat in Lincoln Park, ca. 1890. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library. Right: Swan shaped paddle boats are now available in Humboldt Park. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

The size, shape, and style of boats was extremely important to Frederick Law Olmsted when he began working closely with architect Daniel H. Burnham on plans for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. He had helped Burnham and other fair officials select Jackson Park as the site for the fair and, at the time, its landscape was still largely unimproved. While Olmsted was planning the 630-acre fairgrounds, the design of the various kinds of boats that would sail along the fair’s waterways became something of an obsession for him. A series of letters in the Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Volume IX, The Last Great Projects 1890-1895, illuminates Olmsted’s very specific concerns about boats. Olmsted warned against any boats that would “antagonize” the “poetic object,” and provided suggestions to “make the boating feature at the Exposition a gay and lively one in spectacular effect.” He wanted elegant electric launches with bright awnings. The Elco Electric Launch Boat Company made its debut at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park with 55 launches, each 36' long and powered by battery-driven electric motors. Electricity was a new technology, and fair-goers were excited to see electric lights at the fair and ride on electrically-powered boats.

Electric launch boat near Wooded Island at World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. C.D. Arnold, photographer.

Gondola in lagoon near Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building, 1893. C.D. Arnold, photographer.

Olmsted also suggested that exotic boats should be seen on the lagoons within the fairgrounds. For instance, he recommended the inclusion of Japanese fishing boats “fully equipped with families living on them.” He asked for a “fleet of gondolas” with gondoliers imported from Venice. Olmsted explained that “Venetian gondolas, and any other curious and interesting boats” should “be propelled by sculling, not by rowing.”

Boating had become especially popular in the lakefront parks in the early 20th century. At that time, Jackson Park had retained five of its electric launches, and also had a gasoline-powered barge, and two Naphtha launches. (Naphtha boats were powered by steam, but there were problems with boiler explosions, so they were used only for a short period.) Passengers on electric launches enjoyed a two-and-a-half-mile ride through the lagoons and inner harbor for 10¢ per person. The gasoline barge, which could carry as many as 56 passengers, offered the least expensive of these excursions at 5¢ per person. Meanwhile, rowboats could be checked out in each of the city’s larger parks, usually for the cost of 15¢ an hour for a two-oar boat or 25¢ for a boat with four oars.

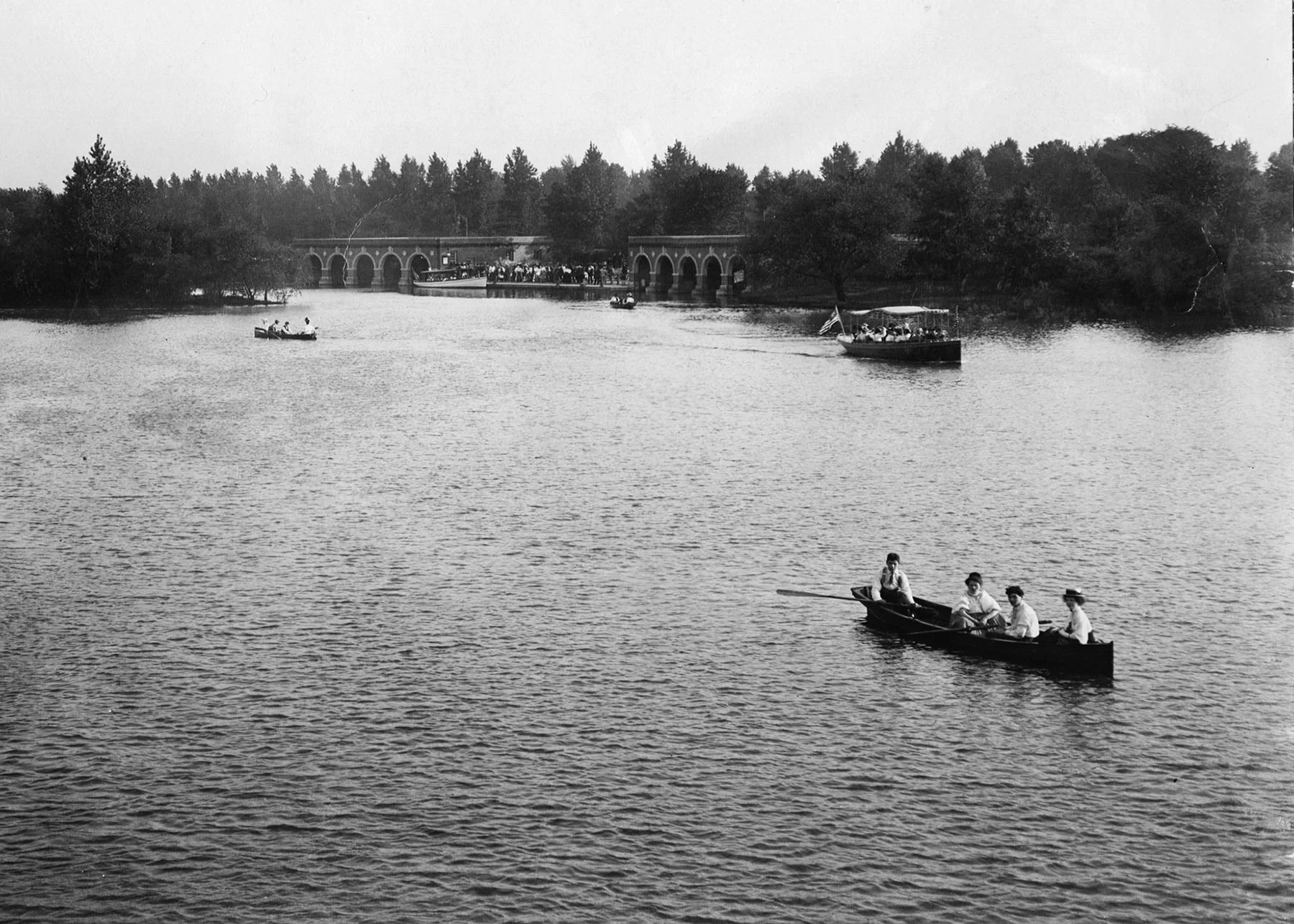

View of Jackson Park’s West Lagoon with the arched electric launch boathouse in the background, ca. 1910. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, LSW-i29467

View of Outer Harbor looking towards Jackson Park Yacht Club. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

By the 1920s, increasing numbers of affluent Chicagoans were able to buy their own motorboats and sailboats, and mooring facilities in Jackson and Lincoln parks began to expand. A few yacht clubs had already been around for decades. These included the Chicago Yacht Club, the longtime sponsor of the annual Chicago to Mackinac Race. Several new clubs began to form. During that period, the park commissions did not allow yacht clubs to build permanent clubhouse structures. Several clubs got around the rules by building their facilities on floating barges. For example, the Chicago Yacht Club’s 1923 clubhouse, designed by architect George Nimmons, was built on a jetty-like structure at the southwest edge of Belmont Harbor. A decade or so later, rules were relaxed, and many of the yacht clubs transformed their clubhouses into dryland park structures.

During the Depression era, only a limited number of Chicagoans could afford to own and moor a private boat. But the public had many other opportunities to enjoy boating in the parks. By this time, hundreds of rowboats could be rented in the seven large parks that had lagoons. In addition, Jackson Park’s electric boat concession operated 26 launches at rates that ranged from 50¢ to $1 per half-hour, depending on the number of passengers. Water carnivals had also become popular. In 1935, the newly-formed Chicago Park District organized a Water Carnival in Garfield Park with its own Venetian Night featuring water floats that were made by park patrons. That event took place annually until WWII.

“Taj Mahal” Water Float in Garfield Park, ca. 1938. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library.

Carnival of the Lakes in Burnham Harbor, 1936. Chicago Park District Records: Photographs, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library

The Chicago Park District held a similar but much larger event called Carnival of the Lakes in Burnham Harbor in 1936. This weeklong water festival had broad citywide participation. It featured nightly parades of illuminated water floats, many of which had been produced by participants of Arts and Crafts classes from various parks throughout the city. With nightly audiences estimated at 40,000, the water carnival included the crowning of a queen and demonstrations of fire boat tugs. Naval reserve officers and members of the Coast Guard staged mock battles. Although the Park District had hoped to stage Carnival of the Lakes annually, it took place only one more time, in 1937.

While it’s doubtful that many Chicagoans remember Carnival of the Lakes, it does seem likely that the historic festival inspired both Venetian Night—an annual event which began in 1958 and ended only recently—and the upcoming annual Air and Water Show.

Kayaks on the Chicago River. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

It’s also exciting that the boating tradition continues today as the public can now rent kayaks, canoes, paddle boards, and paddle boats on the Chicago River and in a number of Chicago parks. These include Ping Tom Park (which also serves as a water taxi stop), Clark Park, Northerly Island, Eleanor Park (Park 571), Humboldt Park, and several beaches in Lincoln and Burnham Parks. Since the summer’s only about half over, I hope you’ll have a chance to enjoy boating at one of these sites sometime soon!