One of the beautiful curving drives in Gillson Park. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Tippy, a new friend named Simone, and Stella enjoying Gillson Park’s Dog Beach. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

On some of the beautiful days we’ve had this fall, my sister and I have met at Gillson Park in Wilmette for doggy playdates with our cousin pups, Tippy and Stella. Located on the lakefront, northeast of the iconic Baha’i Temple, the 60-acre park is extremely lovely. Though I had only visited Gillson Park a few times over the years, people had often asked me if it had been designed by the renowned Prairie-style landscape architect Jens Jensen. With curvilinear drives, lawns edged by informal groupings of trees and shrubs, and beautiful historic stonework, including a council ring, Gillson Park looks and feels like many of the greenspaces created by Jensen. While there is no documentation to suggest that he designed Gillson Park, I have discovered that the greenspace was produced in stages by talented, though essentially forgotten, landscape architects who were likely inspired by Jens Jensen.

Some of Gillson Park’s stonework emulates the work of the pre-eminent Prairie style landscape architect, Jens Jensen. The park even has an example of Jensen’s favorite element—the council ring. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Currently, planning initiatives are underway for Gillson Park, and some community members have concerns about the potential changes these plans may bring. Learning about these issues made me curious about Gillson Park’s history. Here’s what I uncovered. During the early 20th century, landscape architects Benjamin E. Gage, Charles D. Wagstaff, and Robert E. Everly, each highly respected in their day, reshaped “filled land” to create the park. It's a fascinating story, so I’d like to share more of what I’ve found.

Although Gillson Park has a naturalistic-looking landscape, the greenspace is composed of “made land.” Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Originally known as Washington Park, Gillson Park was created more than a century ago as part of an ambitious engineering project. In the early 1900s, Col. Robert R. McCormick, President of the Chicago Sanitary District, began spearheading the development of the North Shore Channel, a drainage canal that would link the North Branch of the Chicago River to Lake Michigan. This project involved excavating and dredging a ditch that would extend from the river’s North Branch at Lawrence Avenue in Chicago to the lakefront in Wilmette at its border with Evanston. As explained by the Wilmette Park District, Col. McCormick noted in 1907 that, along with the eight-mile-long drainage canal, the project “would result in about 22 acres of ‘made land’ dumped into Lake Michigan between Washington Avenue and the canal inlet,” and that a park district could be established under state law to make use of the ‘made land’ for “park purposes at no cost.”

Excavations for the North Shore Channel near Linden Avenue in Wilmette, 1908. Photo courtesy of Metropolitan Water Reclamation District.

The Chicago Sanitary District project included the construction of bridges to cross the canal at various intervals. To control the flow of water and prevent sewage from contaminating the lake and drinking supply, a pumping station was incorporated into the design of the Classically-styled Sheridan Road Bridge in Wilmette. Constructed between 1908 and 1910, the pumping station was tucked into the lower level of the bridge.

Drainage Canal Bridge, Sheridan Road, ca. 1910. Courtesy of the Wilmette Historical Museum.

In 1911, the newly formed Wilmette Park Board officially took possession of the unimproved park site. Transforming the filled land into greenspace proved to be quite challenging. An article entitled “Lawn Making in Reclaimed Park,” published in Park and Cemetery Magazine in 1917 explained, “The top of this twenty acres was of course the bottom of the excavation of the channel and was hard blue clay.” The author noted that “the obstacles presented in transforming this pile of clay, which had ridges and valleys making differences in elevation of approximately fifteen or twenty feet, seemed to present difficulties that might be impossible to overcome.”

Benjamin E. Gage created the “Landscape Plan for Washington Park,” around 1915. From Park and Cemetery Magazine.

To address these challenges, the park board hired Benjamin Emmons Gage (1881-1956), a professional landscape architect and engineer. Prior to establishing his own practice, Gage had served as vice-president of the Peterson Nursery (one of Chicago’s oldest nurseries). He and his family had moved to Wilmette around the time that the park board commissioned him to devise a method of treating the fill and to prepare an original plan for Washington Park. Gage’s treatment included pulverizing the hard clay, planting a succession of cover crops such as peas, oats, millet, and rye, and then plowing the crops under to enrich the soil. After three years, the site was ready to be graded. Following Gage’s plan, laborers built a curvilinear circuit drive, created lawn areas, and planted trees and shrubs. The roadways which made up the original circuit drive, known as Middle and Upper Drives, remain today.

This photograph was taken soon after the park’s original drives and walks were created and initial trees were planted, 1917. Wilmette Historical Museum.

While briefly serving as superintendent of the Wilmette parks, Benjamin E. Gage also designed Vattmann Park at 15th Street and Lake Avenue. He continued to promote his services as a landscape advisor and later became involved in golf course and real estate development. (Interestingly, his son, Benjamin Austin Gage (1914-1978) was a radio star who married Esther Williams, the famous swimmer and actress, in the 1940s.)

Benjamin Gage’s design for Vattmann Park included a shelter, wading pool, and fountain. The American City, 1918.

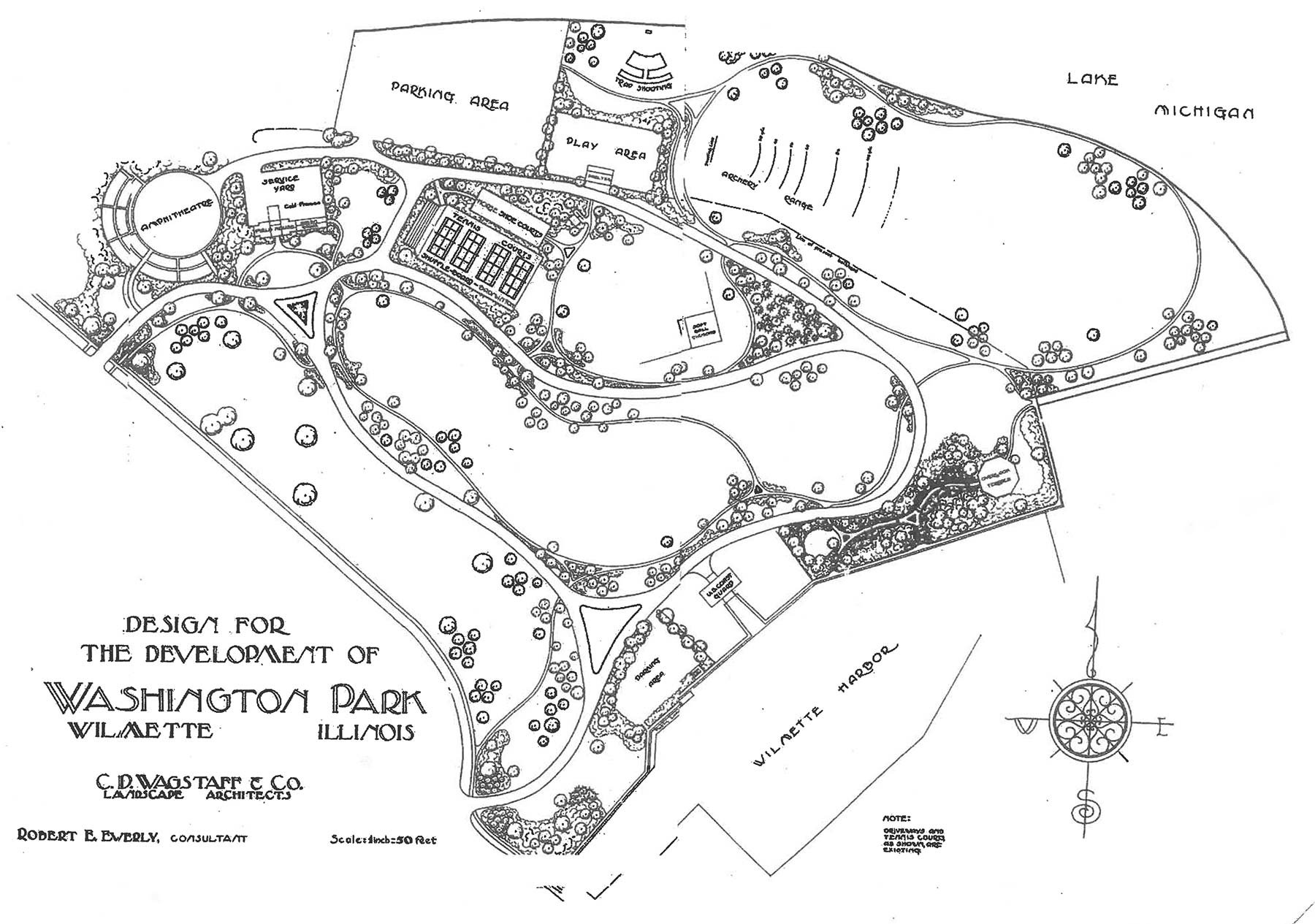

In the 1920s, the Sanitary District beautified the harbor in Washington Park, however few other improvements were made to the greenspace during that decade. The Park Board then focused on enlarging the park through land acquisition and fill projects. After more than doubling Washington Park’s size to 59 acres, the board needed a new comprehensive plan for the lakefront greenspace. In the mid-1930s, the Wilmette Park District retained landscape architect C.D. Wagstaff with Robert E. Everly as consultant to produce the plan. Wagstaff and Everly created a thoughtful scheme that incorporated an array of recreational features as well as the existing circuit drive and lawn areas into a lovely naturalistic landscape.

Design for the Development of Washington Park, Wilmette by C.D. Wagstaff and Robert E. Everly, January 23, 1937.

Charles D. Wagstaff, The Illinio: A Yearbook Produced by the Junior Class of the University of Illinois, 1917.

Although Wagstaff and Everly are names that are not widely remembered today, they should be. Both made important contributions to American landscape architecture. Born in Kansas and raised in Indiana, Charles Dudley Wagstaff (1894 -1977) received a degree in landscape architecture from the University of Illinois. After serving in the U.S. Navy for two years, he moved to Evanston and established C.D. Wagstaff & Co., a landscape architecture firm that specialized in golf courses. Considered one of the area’s pre-eminent golf course designers, Wagstaff produced dozens of public courses and country club grounds, including the Tam O’Shanter Golf Course in Niles, the Kildeer Country Club in Long Grove, and a 36-hole course for the University of Illinois. Wagstaff also designed parks, campuses, and residential landscapes. Among his works of the 1930s were landscapes for A Century of Progress (Chicago’s second World’s Fair) and the Great Lakes Exposition in Cleveland, as well as the grounds for the Morse estate in Lake Forest and for a model house in Winnetka.

Robert E. Everly, “Named U.S. Park Representative at Meeting in London,” Chicago Tribune, April 28, 1957.

Landscape architect and engineer Robert Edward Everly (1905-1996) knew Jens Jensen and was deeply inspired by him. Everly was born in Dubuque, Iowa, and moved to Chicago sometime before 1930. According to biographical information provided by his family, during his early years, Everly worked on a landscape surveying and construction crew. (It seems quite possible that he worked on projects that were designed by Jensen.) Jens Jensen must have been quite impressed with Everly because in 1930 he recommended his younger colleague for the position of park superintendent for Glencoe, Illinois. This job reference most certainly held weight. Jensen, who had designed a number of parks in Glencoe during the 1910s, was held in high esteem throughout and beyond the North Shore.

Through his work as the Glencoe Park Superintendent, Everly followed Jensen’s philosophies and carried out projects suggested by his mentor years earlier, such as the school-park plan (a concept that Jensen set forth in the 1910s advocating that school grounds and parks be combined). Everly played a nationally prominent role in park design and management, and in addition to serving as Glencoe’s park superintendent for 30 years, he formed a consulting firm with John McFadzean, Superintendent of the Glencoe School District. The firm of McFadzean, Everly & Associates was active for decades designing parks, zoos, and school grounds throughout the nation.

Left: Stratified stone wall and steps in Gillson Park. Photo by Julia Bachrach. Right: The Jensen-designed stratified stonework in Columbus Park, Chicago, ca. 1925.

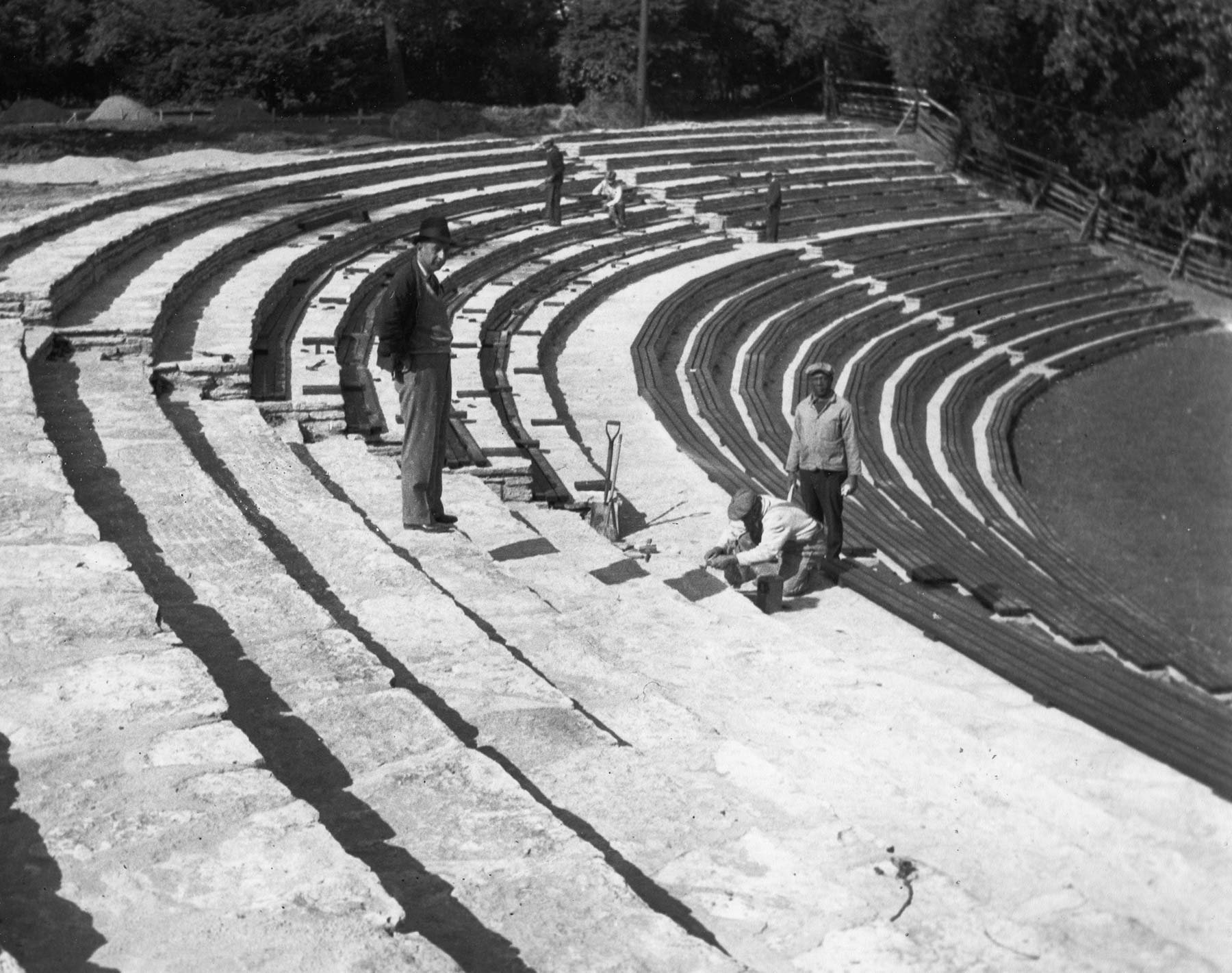

Wagstaff and Everly’s mid-1930s plan for Gillson Park doesn’t specifically show stonework details such as the council ring. Despite this, it seems likely that Everly was responsible for these naturalistic elements that emulate Jens Jensen’s work. Gillson Park also has stonework that is more characteristic of the parks created by the Works Progress Administration (W.P.A.) of the 1930s. The Gordon Wallace Bowl, known originally as the Washington Park Amphitheater—which is clearly shown in the Wagstaff and Everly plan—was a W.P.A. project.

Construction of the amphitheater, 1937. Courtesy of the Wilmette Historical Museum.

Gordon Wallace, who served as Wilmette Park Superintendent from 1936 to 1968, oversaw the amphitheater’s original development in 1937 as well as renovations to the structure to include a permanent stage a decade later. Rehabilitated again in the 1980s, the Wallace Bowl remains a cherished community asset.

Overlook Drive looking south. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Another important figure in the development of the park was, of course, Louis K. Gillson. A patent attorney, Gillson was the first president of the Wilmette Park Board and served on the board for more than 25 years. When Gillson died in 1956, Washington Park was renamed in his honor. Gillson Park has stood the test of time. It accommodates a wide range of recreational activities while remaining a gorgeous naturalistic landscape. Offering a sense of calm and tranquility, the lakefront haven has been especially important during this stressful age of COVID-19.