Chicagoans have played cricket, baseball, and football on Washington Park’s pastoral meadow, known as the South Open Green, for well over 100 years. Photo by Lucas Blair, 2009.

During my many years as Chicago’s park historian, I never became bored with my topic. One reason I’ve always found public parks so fascinating is that, historically, as sports and other leisure time trends changed, designers often found ways to incorporate new facilities without compromising the integrity of the landscapes. The Chicago Museum of Design recently opened an exhibition entitled Keep Moving: Designing Chicago’s Bicycle Culture. In conjunction with this exhibit, I will give a presentation called Beauty and the Bike: The Impact of Recreational Changes on Park Designs on December 6, 2018. More information on the program, which is free and open to the public, can be found at designchicago.org.

Children playing in and along Washington Park’s meadow, ca. 1900. Barnum & Barnum Photographers. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, ICHi-15585.

As shown by this plan, the great meadow called the South Open Green was the earliest parts of Washington Park’s landscape to be completed. The Western Division of South Park, 1880.

During the early 1870s, when Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) and Calvert Vaux (1824-1895), creators of New York’s Central Park, began laying out Chicago’s South Park (now Jackson and Washington Parks and the Midway Plaisance), they expected the enormous green space to be used primarily for strolling, picnicking, boating, and ball playing. In fact, in their Report Accompanying Plan for Laying Out South Park, the designers wrote, “Among the purposes for which public grounds are used is that of an arena for public sports such as base ball, foot ball, cricket, and running games such as prisoner’s base.”

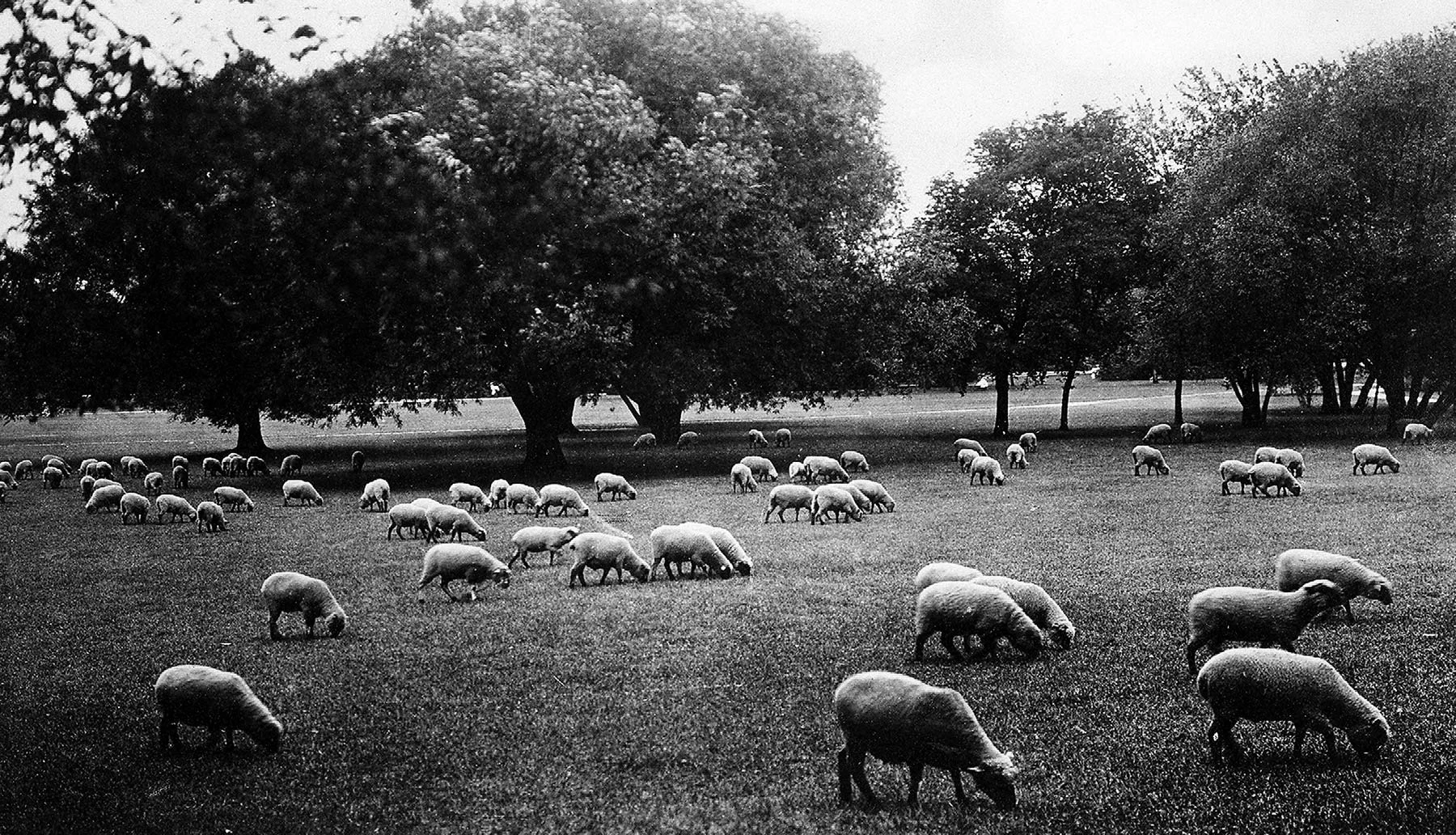

In the Western Division (Washington Park), Olmsted & Vaux designed a large pastoral meadow bordered by trees and shrubs. This South Open Green, approximately 150 acres in size, would accommodate baseball and other games and provide a place where sheep could freely graze and roam to enhance the pastoral character of the landscape. They wrote “turf is much more favorable to the skill and comfort of those engaged in the exercises and more agreeable to the eye of spectators than gravel, it is also less costly.”

Sheep in Washington Park’s meadow, ca. 1910. Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Chicago Park District Archives, Photos.

Within a short time, a range of new activities were gaining popularity, and park administrators often at first considered them to be intrusions. For example, growing numbers of “wheelmen” wanted to ride their bicycles in the parks in the late 1870s and early 1880s. Fearful that “scorchers” would ruin roads and cause injuries to innocent bystanders, Lincoln Park’s commissioners passed ordinances in 1880 and 1881 to prohibit cycling in the park. Their worries weren’t unfounded. The high-wheeler bikes (also known as penny-farthings) had no gears, and as their pedals were attached directly to the large front wheel, riders often spooked horses and caused accidents.

This 1880s photograph of cyclists in Lincoln Park was published in an Annual Report of the Chicago Park District, 1976.

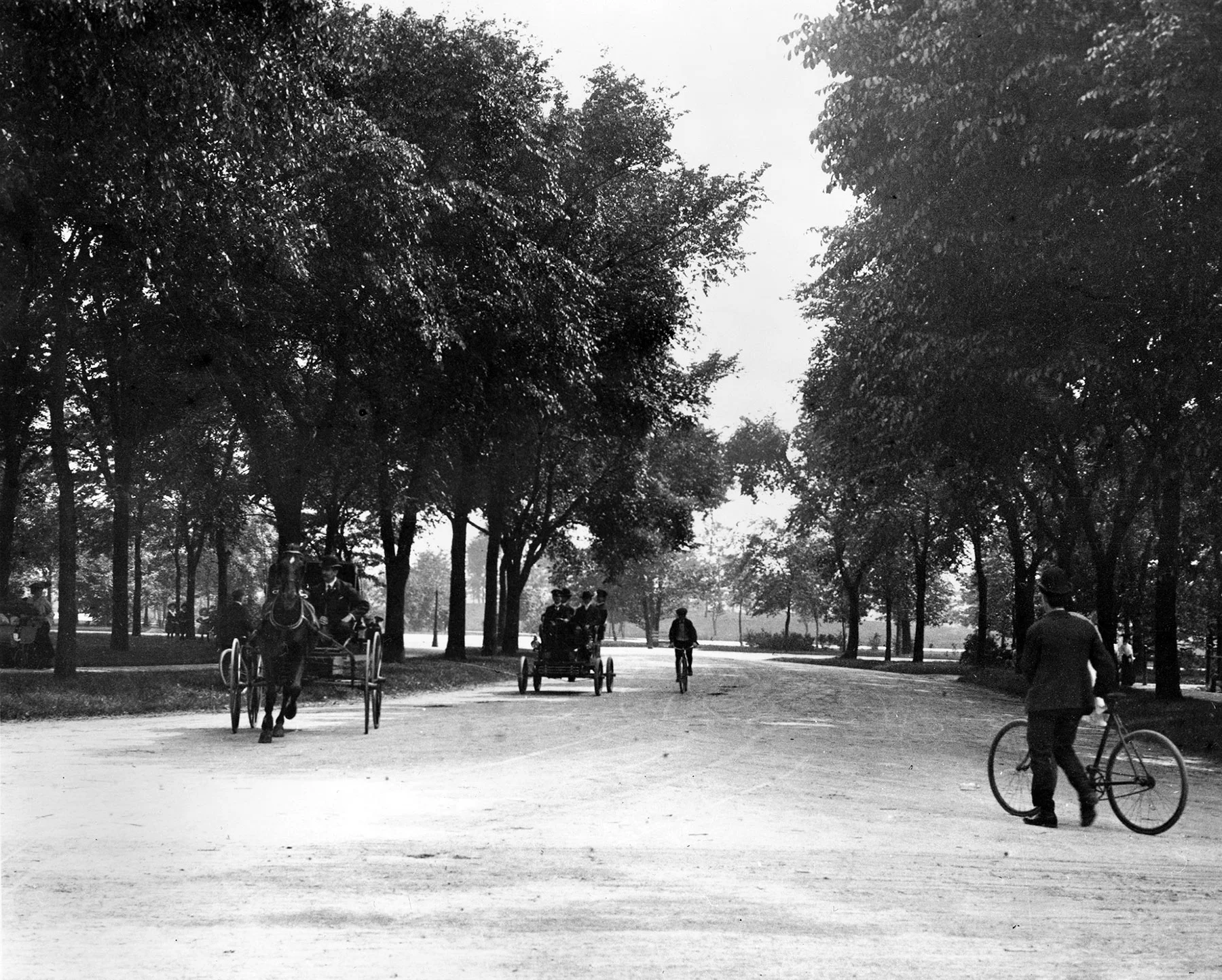

During the late-1880s, “safety bicycles”—the kind with two equal-sized wheels like we ride today—not only became available, but also affordable to middle-class Chicagoans. By then, restrictions against cycling in Lincoln Park had been lifted, as had similar rules in other parks. Bicyclists began to throng Chicago’s parks.

By the mid-1890s, bicycles often shared park roads with horses and carriages, as shown in this photo of Garfield Park, ca. 1895. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum iCHi-51168.

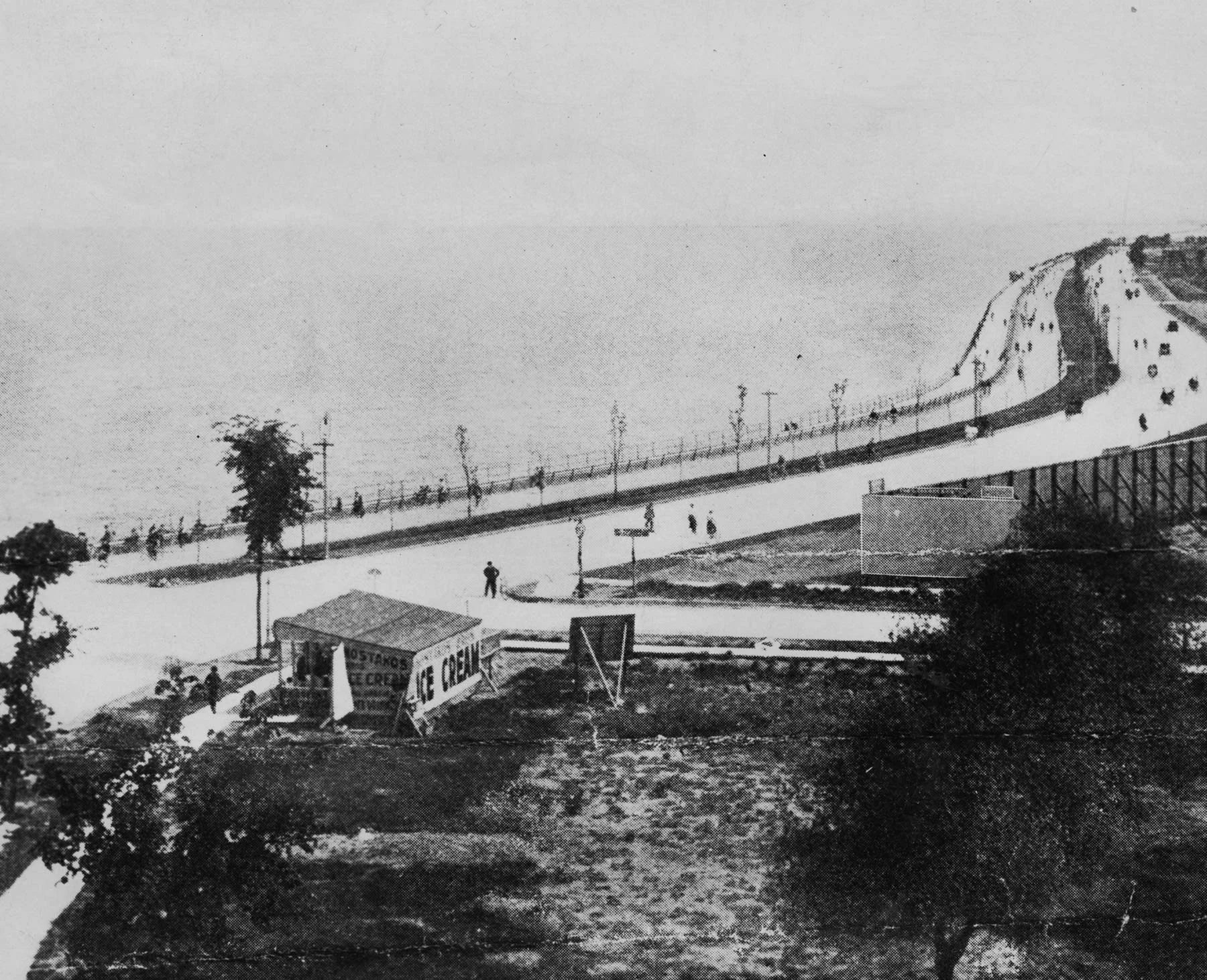

In the early 1890s, the Lincoln Park Commissioners began making plans for stretches of bicycle paths along the lakefront, including a 27-foot-wide path along the granite paved beach south of Oak Street. A few years later, they announced an even more ambitious scheme for a landfill extension area north of Belmont Avenue. On September 14, 1895, the Chicago Tribune reported that this project would include two paths adjacent to Sheridan Road (which is now part of North Lake Shore Drive)—a 16-foot-wide bicycle path and 14-foot-wide bridle path. The Lincoln Park Board President Andrew Crawford described the 4,800-foot-wide promenade and double paths as “the grandest thing in the world, being considerably longer than that at Naples, which attracts so much attention.”

This stretch of Sheridan Road (now Lake Shore Drive), north of Belmont Avenue, included one of Chicago’s earliest lakefront bicycle paths, ca. 1900. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum iCHi- 17819.

Along with bicycling, many other forms of “active recreation” were on the rise in late 19th century Chicago. At the time, Germans accounted for the city’s largest ethnic population, and many were enthusiastic members of clubs that encouraged physical and moral fitness called Turnverein. In 1895, the Turnverein Vorwaerts, a Turners club located at W. Roosevelt Road and S. Western Avenue, petitioned the West Park Commissioners for an “outdoor gymnasium and public swimming bath” in Douglas Park.

“New Gymnasium and Natatorium at Douglas Park,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 20, 1896.

Agreeing to the request, the commissioners soon hired Bohemian immigrant architect Frank Randak (1861-1926) to design the facility. He produced a brick natatorium with turrets, pitched roofs, and open courtyards that had separate outdoor pools for men and women. Randak’s complex included a quarter-mile-long running track with gymnastics apparatus—parallel and horizontal bars, trapezes, swings, vaulting horses, and ladders in the center of the oval.

With separate pools for men and women, the 1896 Douglas Park natatorium was the first swimming facility in Chicago’s parks. This photo of the women’s pool dates to 1914. Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Chicago Park District Archives, Photos.

Numerous athletes used the Douglas Park Natatorium and its oval track including the Earls, an African-American track team of late 1930s. Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Chicago Park District Archives, Photos.

In celebration of the natatorium’s opening, the West Park Commission held an extensive dedication ceremony. The event included a parade from Union Park to Douglas Park in which members of numerous Turners clubs marched alongside Polish and Bohemian athletic club members and representatives of trade unions. Towards the rear of the procession, members of the Chicago Bicycle Club rode past cheering crowds.

The impact of changing recreational trends accelerated over the course of the 20th century, a topic I will address in my December 6th presentation. The program, which will take place from 6 to 7 p.m., is open and free to the public. Hope to see you there!