Rededication of Jane Addams Monument near Widow Clarke House in Chicago Women’s Park and Gardens, 2011.

Beginning on Tuesday, September 18, 2018, I will be giving a three-part Newberry Library seminar called Her Story: Women in Chicago History. This seminar features two in-class sessions and a very special tour of the Widow Clarke House and Chicago Women’s Park and Gardens. Registration is still open, and there are a few spaces available. So I hope you’ll consider registering at newberry.org/F18HerStory.

Chicago Women’s Park and Gardens new signage. Photo courtesy of Jell Creative, Inc.

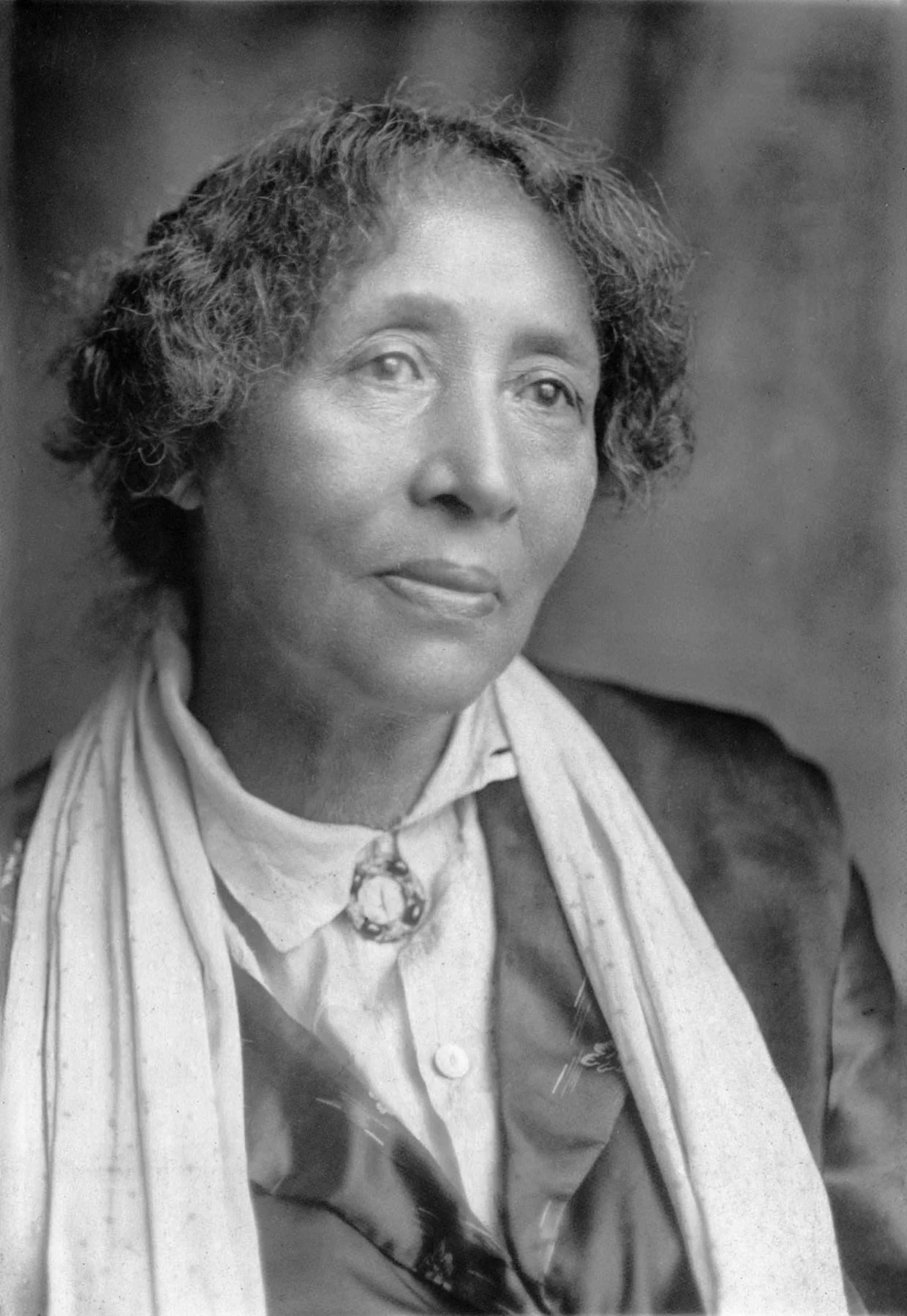

Ida B. Wells Barnett. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, i12868.

Although women’s contributions to Chicago history have long been overlooked, things are starting to change. This July, Chicago’s City Council passed an ordinance to rename Congress Parkway in honor of civil rights leader, anti-lynching crusader, and journalist Ida B. Wells (1862-1931). Let’s hope that this marks the beginning of a movement to officially name more Chicago streets for noteworthy women.

My own initial “deep dive” into women’s history was spurred by such a movement. Fifteen years ago, while serving as the Chicago Park District (CPD) historian and planning supervisor, I received a note from Maria Saldana, the CPD’s first female board president. The note said that she and Cindy Mitchell (a founder of Friends of the Parks who also then served on the CPD board) wanted me to create a list of all Chicago parks named in honor of women.

Chicago Park District Board of Commissioners, 2003. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

When I compiled the list, I found the results somewhat surprising. At that time, there were 555 parks in Chicago. I discovered that while approximately 350 of them were named for individuals, only 27 honored women. This paltry list included two parks named for Chicago’s internationally renowned social reformer, Jane Addams, several for developers’ wives or daughters, and a few for girls who had died tragically. Houston Park, which had been named in 1991, was then one of the few parks that actually honored a female who had made substantial contributions to Chicago history. Reverend Jessie ‘Ma’ Houston (1899-1980) was the first local woman allowed to minister to prisoners on Death Row.

Jessie ‘Ma’ Houston Park. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

The park renaming assignment was exciting for me. I feel inspired when I learn about seemingly ordinary people who do great things. Women, especially those of color, have often had to overcome tremendous obstacles to achieve success. So I find their contributions to be especially meaningful.

Bessie Coleman worked as a manicurist on Chicago’s South Side before she became the nation’s first female African American pilot. Wikicommons photo, 1922.

When I started, I had hoped to bring dozens of naming proposals to the CPD board as quickly as possible. But I also wanted to make sure that I did my homework. The CPD has a well-defined naming procedure in Chapter 7 of its official Code. To help guide this project, I developed a methodology specifying that, in addition to meeting the Code’s park-naming criteria, candidates should also have lived, worked, or performed community service within a three-mile radius of the proposed park site. I thought this would make the naming initiative more meaningful to residents of the surrounding communities, and decisions would be somewhat less arbitrary. (Appropriate sites for naming or renaming were identified beforehand.)

Lucy Parsons, 1920. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, i12071.

In April of 2004, I proposed a group of parks to be renamed for nine significant Chicago women. This ambitious proposal called for parks honoring: radical labor leader Lucy Parsons; architect Marion Mahony Griffin; poet Harriet Monroe; musicians Lillian Hardin Armstrong and Mahalia Jackson; playwright Lorraine Hansberry; social reformer Esther Saperstein; physician Margaret Hie Ding Lin; and scientist Chi Che Wang. Eventually, most of these important women would be honored with her own park. But, the procedure didn’t go as easily or as smoothly as I had hoped.

The CPD’s naming process involves substantial input from community members and political leaders. There were a variety of reasons that specific proposals did not move forward. The most controversial of the initial group was the proposed naming for Lucy Parsons, whom the Chicago Police had once described as “more dangerous than a thousand rioters.” In 2004, the Fraternal Order of Police filed a letter of objection against naming a park for a “known anarchist,” implying that her husband Albert Parsons was responsible for deaths (including those of policemen) caused by a bomb thrown during the Haymarket protests of 1886. (That accusation was disproved long ago. Albert Parsons was hanged, and posthumously exonerated.)

Lucy Parsons Park. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

When I made the naming proposal, there was growing interest in Lucy Parsons’ importance to Chicago history. She helped found the Industrial Workers of the World, and was a prolific writer and advocate for labor and other social reforms. Artist Marjorie Woodruff had created a temporary artwork in Wicker Park called Spiral: The Life of Lucy E. Parsons in Chicago 1873-1942, and the City of Chicago had installed a tribute marker to Albert and Lucy Parsons in front of their home on N. Mohawk Street. A detailed entry on Lucy Parsons had also been published in the book Women Building Chicago 1790-1990, edited by Rima Schultz and Adele Hast. (This extremely well-documented and written book inspired a number of the park names that later moved forward.)

Mahalia Jackson. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum, i34969.

In May of 2004, the CPD Board made its first approvals to name parks for noteworthy Chicago women. But, only two of the proposed nine names were accepted: Lucy Parsons and Mahalia Jackson. Lucy Parsons Park is located at 4712 W. Belmont Avenue, about two miles west of the home where she lived for many years at the end of her life. (Interestingly, last year, the Chicago City Council dedicated an honorary Lucy Gonzalez Parsons Way at N. Kedzie and W. Schubert Avenues, even closer to her home.) Mahalia Jackson Park, at 8385 S. Bickhoff Avenue, lies only four blocks from the home she purchased at 8358 S. Indiana Avenue in 1956.

Left: Marion Mahony Griffin Park was dedicated in 2015 after several earlier failed attempts to name a park for her. Right: Boulder in Marion Mahony Griffin Park. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Although the women’s naming project proved to be more difficult than I had expected, many friends, colleagues, community members, and civic leaders jumped on board. The CPD board remained committed, and over the years, there were many successes. As of 2017, more than 40 additional parks had been named or renamed for significant Chicago women. (As this is still less than 20% of all parks named for people, I hope the trend will continue!)

Leslie Recht at Exhibit Dedication in Chicago Women’s Park and Gardens, September 14, 2017.

Another milestone last year was the dedication of new signage and an exhibit in Chicago Women’s Park and Gardens. This project was the brainchild of park activist Leslie Recht. I was honored to work with her, Jell Creative Inc., and several colleagues at the CPD on this project before I resigned last spring. (The installation was also made possible by Alderman Pat Dowell.)

Today, a new movement is afoot to create local monuments honoring women in Chicago history. Depending on how one counts, as of now, there are five outdoor public monuments to noteworthy women in our city’s history. These include the Cheney-Goode commemorative bench on the Midway Plaisance; the Helping Hands monument to Jane Addams in Chicago Women’s Park; Lincoln Park’s Fountain Girl, also known as the Frances Willard monument; the Laura Liu sculpture in Ping Tom Park; and a Gwendolyn Brooks installation in Gwendolyn Brooks Park. There is no doubt that Chicago also will soon have an Ida B. Wells Monument.

Gwendolyn Brooks Monument in her eponymous park. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

I hope you’ll join me at the Newberry Library to learn more about many fascinating women in history. Through this seminar, I hope that we can put our heads together and find new ways to increase awareness of Chicago’s great matriarchs.

Register at newberry.org/F18HerStory.