The Imperial Towers is a Mid-Century Modern high-rise with a “Far Eastern” flair. The swirling, abstract forms of its mosaic panels represent Japanese garden elements. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

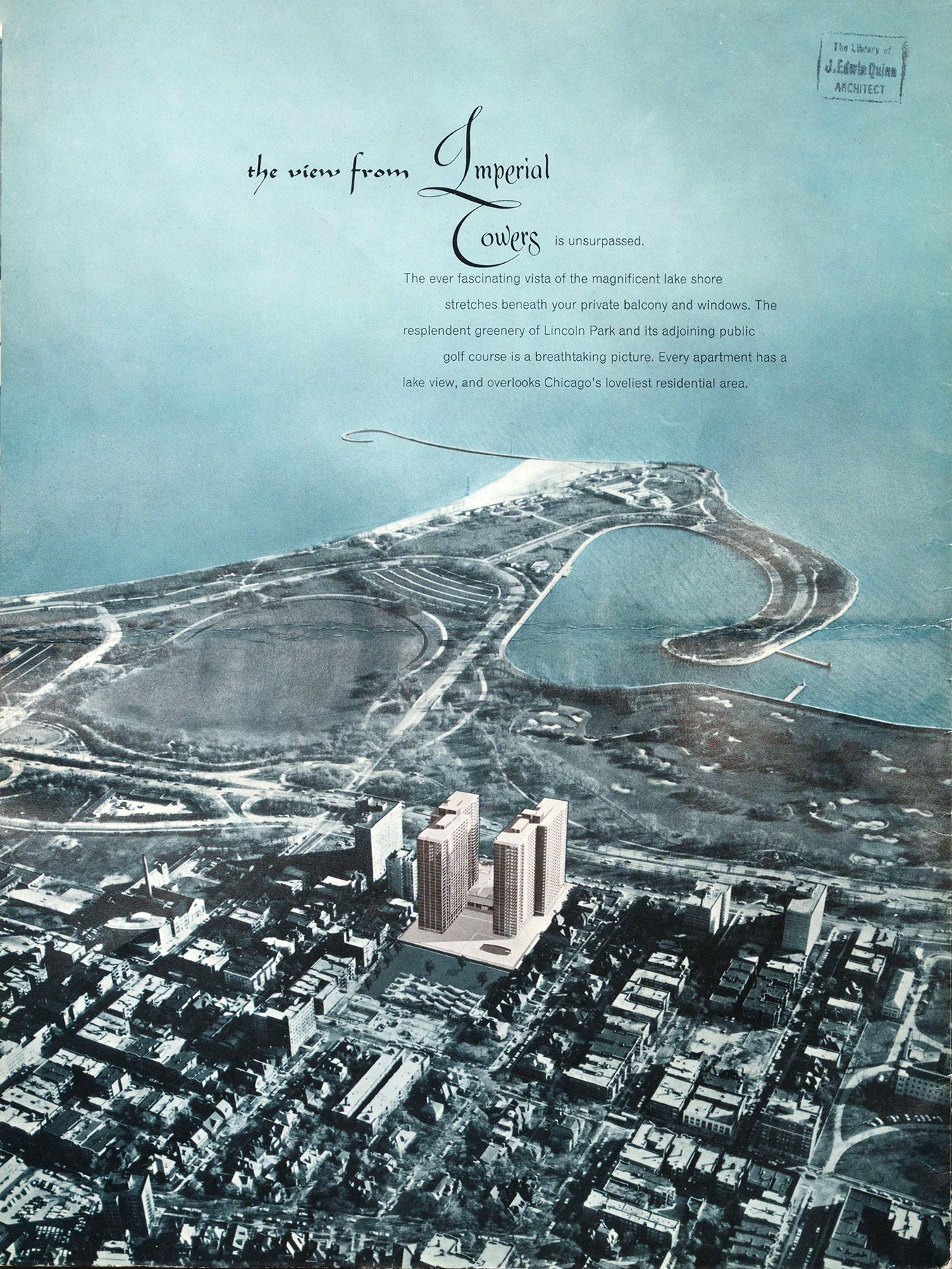

Imperial Towers: A World Apart, marketing pamphlet produced by Powell, Schoenbrod and Hall. McNally and Quinn Records, Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson & Burnham Archives, Series 1, OP 1.17, ca. 1961.

I must confess—for many years I thought that most 1960s high-rises were bland and repetitive. But now that I’ve had the chance to research architecture along the N. Lake Shore Drive corridor, I realize that I was SO WRONG! One of my favorite discoveries of that era is the Imperial Towers at 4250 N. Marine Drive. Completed in 1962-63, this fascinating complex is neither bland nor repetitive.

Since the early 20th century, developers had built luxury apartments along N. Lake Shore Drive to capitalize on the great views of Lake Michigan and close proximity to Lincoln Park. Construction projects halted during the early years of the Depression and by the end of World War II Chicago was in the midst of a major housing crisis. A robust rental market and new financing opportunities spurred the development of glassy lakefront apartment structures geared towards middle-class renters in the early 1950s. A decade later, as the market remained strong, many developers erected larger complexes with various amenities to accommodate automobiles; conveniences such as on-site food stores and beauty shops; and outdoor sundecks with large heated swimming pools.

Left: Accommodations for car owners represented a major priority in the Imperial Towers’ design. Imperial Towers: A World Apart, marketing pamphlet. Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson & Burnham Archives. Right: Contemporary view of Imperial Towers’ front canopy and drop off area. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

Along with including all of these modern amenities, the Imperial Towers’ developer, Albert A. Robin, wanted to distinguish it from the other high-rises that were being built nearby at the time. He did so by working closely with his architects, L.R. Solomon and J.D. Cordwell Associates, to create an elegant modern building that, according to its advertising campaign, was “designed in Far Eastern splendor.”

Cover of the Imperial Towers: A World Apart marketing pamphlet. Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson & Burnham Archives.

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Albert A. Robin (1912-2007) came from modest beginnings. During the early 1930s, he dropped out of college to help his father open a shoe store in Chicago’s Albany Park neighborhood. The business failed, and the younger Robin soon found work at a small commercial real estate firm. Despite the challenges of the Great Depression, in 1935, he printed up business cards and launched the Robin Construction Company. Beginning with a modest $125 contract to build a fence, Al Robin went on to become one of the city’s most successful contractors and developers. He had always loved art, and eventually became a major collector and donor to the Art Institute of Chicago. Robin often brought his artistic spirit into his building developments.

Left: North Tower. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers. Right: Close-up of the abstract mosaic panels that are evocative of Japanese garden elements. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

The abstract flowing shapes of the black and white terrazzo of the lobby floor are evocative of Japanese garden elements. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

The apartment complex’s two staggered towers each comprise a soaring form accentuated by long vertical piers that extend from the ground to the rooftop. At ground level, speckled gray Roman brick first-story walls sit well behind the thin columns, so that the upper stories seem to float above them. The second story features an eye-catching horizontal element that expresses Robin’s “Far Eastern” theme. These are a series of mosaic panels which symbolically represent the flowing lines, island-like forms, course textures, and black lava rocks used in Japanese gardens.

Robin personally went on trips to Japan and Hong Kong to select the building’s original lobby furniture. In addition, the front lobby’s terrazzo floor echoes the abstract patterns of the exterior mosaics and an opaque window above the front desk that features a bonsai tree design.

An etched glass bonsai tree is the centerpiece of the circular window above the lobby desk. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

Robin likely met Solomon and Cordwell through his role as investor and contractor of Sandburg Village, a major urban renewal project in Lincoln Park. Louis R. Solomon (1906-1971), also from a Russian Jewish immigrant family, had attended the University of Illinois on a scholarship. Receiving his architectural degree during the early years of the Depression, he and his siblings formed a small real estate firm in which they bought and remodeled apartment buildings. After WWII, Solomon began specializing in modern high-rise design and development. In 1956, he hired John D. Cordwell (1920-1999), an English-born and -trained architect and planner who had recently served as the City of Chicago’s Director of Planning. The two soon won the competition to design Sandburg Village and they became partners in 1958. (The firm would become Solomon Cordwell Buenz & Associates in 1967.)

Rendering from “Big Marine Drive Project Set,” Chicago Tribune, February 9, 1960.

Robin had intended for Imperial Towers to be a much more ambitious project. He had Solomon and Cordwell prepare initial designs for a $35 million residential six-acre complex with six high-rises that would provide 2,100 rental units. However, the Chicago Public Schools acquired a large part of the proposed site to build Brennemann Elementary School. So Robin had Solomon and Cordwell redesign the project as two 432-unit towers and the construction budget was lowered to $20 million.

Mature honey locusts and other trees in the front landscape have been pruned in a Japanese manner. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

According to long-term residents, this mini “volcano” was originally topped by a gas flame that provided a molten-lava-like element at night. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

The Imperial Towers has three gardens that, according to its early marketing pamphlet, created “a world of exotic beauty.” These include the front landscape that straddles the curved drive, a glassed-in dry garden behind the lobby desk, and a Torii Gate and plantings on the upper sundeck. Miles Berger, author of They Built Chicago: Entrepreneurs Who Shaped a Great City’s Architecture, suggests that a Japanese architect designed the gardens. Unfortunately, the identity of that designer is unknown. It is clear, however, that great thought and attention to detail went into these gardens.

The front garden has several honey locusts, gingko trees, and Japanese maples that are groomed in an elegant manner. A black lava stone grotto gracefully covered with flowing succulent vines emulates a volcano. Nearby rockwork includes a small waterfall. Japanese lanterns, boulders, and other stonework can also be found on both sides of the curving driveway.

The Japanese dry-garden is tucked behind the glassy lobby. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

As is traditional in Japanese dry gardens, the Imperial Towers’ glassed-in space features small stones emulating water and larger rocks and boulders that symbolize mountains. When first created in the 1960s, the dry-garden was likely raked to form water-like ripples in the gravel. The dry-garden also includes lanterns, small bonsai trees, a simple Japanese pavilion with a zig-zag plank bridge, and a traditional boundary wall with a red-tile faux awning. The dry garden is for viewing only, but it can be seen from many vantage points.

Torii Gate and Japanese garden on sundeck. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers.

In addition to an impressive Torii Gate and cabana structure, the sundeck has several Japanese garden elements. Lushly planted beds represent island-like forms. Stone is used artfully, with small pebble-like edging along some plantings, boulders that provide focal points, and stepping stones that stretch across turf. Trimmed azaleas, magnolias, dwarf Mugo pines, pachysandra groundcover, and beds of iris enhance the Japanese effect. Along with the Torii Gate and garden, the sun-deck features an Olympic-sized pool, highly-touted in the 1960s and well-loved by residents today.

“Display Ad-159,” Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1963, p. C 9.

During its early history, the Imperial Towers’ tenants included many young professionals, a number of whom were active in Lakeview’s Jewish community. Along with doctors, lawyers, and business owners, several teachers lived in the building. The most famous was Beverly Marston Braun (1930 -2010), who had taught at Stone Elementary School, and starred on Chicago’s Romper Room television show for several years in the early 1960s.

Al Robin sold the Imperial Towers in 1977, and within a short time, it became a condominium complex. Today, many residents feel that the building is—just as early advertisements claimed—“America’s most fabulous building.”