The 1906 Joseph Downey House, a large classic American Foursquare, is now the Berger Park Cultural Center.

Last month, when I blogged about the work of architects Huehl & Schmid, I highlighted two American Foursquares produced by the firm—the Stayart and Zuncker houses. These fine brick residences are actually somewhat different from one another, and they made me think about how the Foursquare is such a fascinating house type. The earliest versions appeared as if by magic in the early 1890s and the house type soon became very popular across the country. I’m definitely a fan of these houses—in fact, I live in one! So, the American Foursquare is the star of this month’s blog.

Huehl & Schmid’s Foursquares include the Stayart House at 536 W. Barry Avenue (left) and the Zuncker House at 2312 N. Kedzie Avenue (right).

The American Foursquare building type generally refers to a two-story house with a square floor plan that includes four rooms on the ground level and four rooms on the second story. They are often cube-shaped in form with a pyramidal hipped roof and a center dormer. One thing I like about the house type is that there are many variations, including gable-roofed versions. Foursquares tend to have wide front porches with the entry door in the center or on one side. The houses were constructed of various materials, including stone, brick, and frame. The wood-frame buildings could be finished with clapboards, shingles, stucco, or a combination of these. And best of all, Foursquares ranged from modest cottages to spacious mansions, and thus provided (and continue to provide) homes to people of varying means.

An exuberant Queen Anne style residence of the late 1880s, the Robert and Mary Childs House is located in Hinsdale, IL. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Many architectural historians believe that the Foursquare emerged as a reaction to eclectic Victorian house styles, such as the Queen Anne, which had been popular for more than two decades at the end of the 19th century. In a master’s thesis entitled The Four Square House in the United States, Thomas Walter Hanchett wrote: “The gaudy complexity of the Queen Anne brought a widespread revolt which set the course of American design from the 1890s through the First World War. Architects and the general public as well cried out for a simpler, more sensible residential architecture.” In contrast to Victorian houses, Foursquares featured clean lines, simple and often minimal ornamentation, and an efficient use of space. The new house type quickly sprouted up in cities, suburbs, and even rural areas across the country.

American Foursquares in Parkersburg West Virginia. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, 2015. Courtesy of West Virginia Collection, Carol M. Highsmith Collection, Library of Congress.

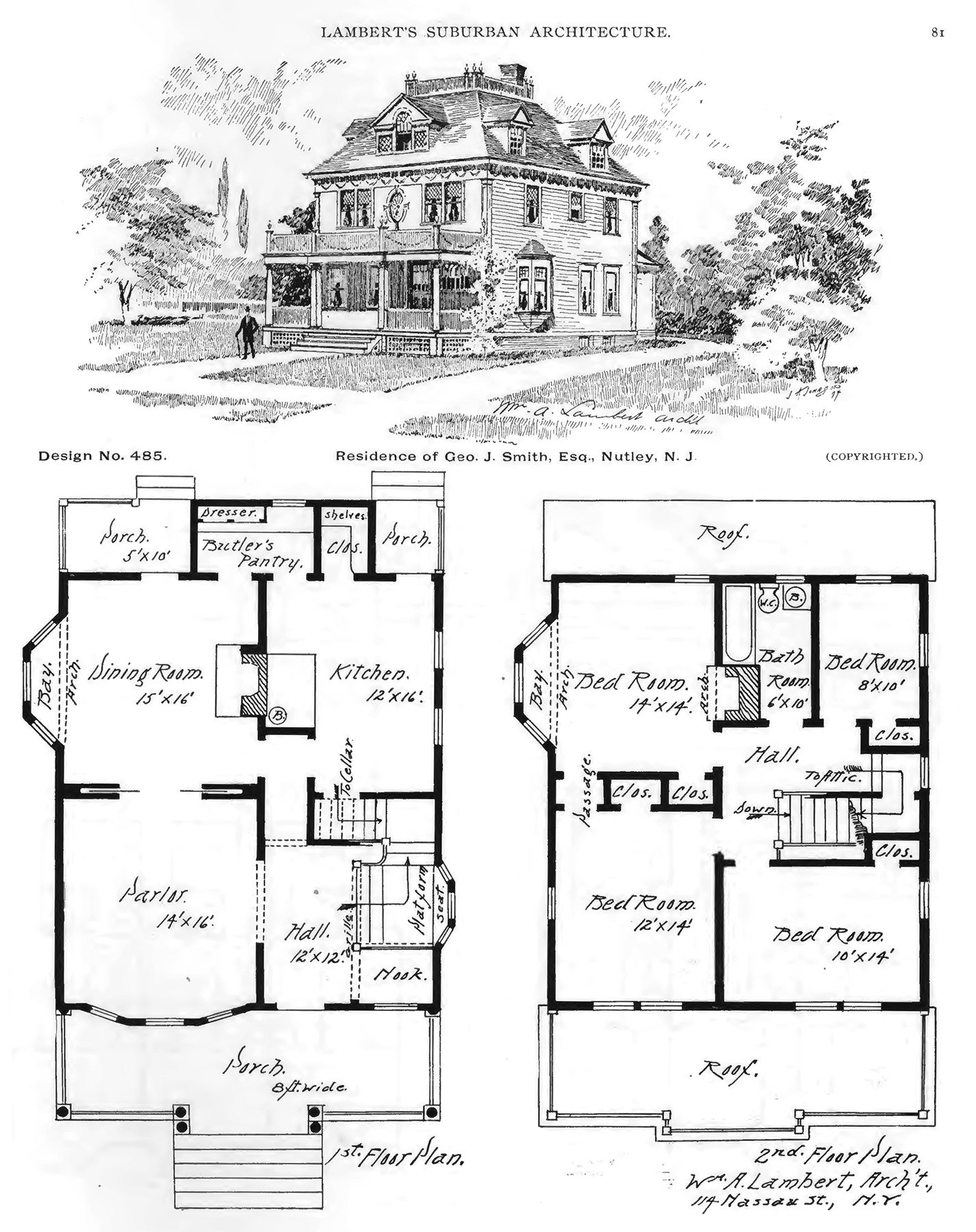

One of the reasons for the rapid spread of Foursquares in the 1890s and 1900s was that the house type began to be featured in architectural journals, pattern books, and even department store catalogs of that period. A blog entitled “Looking Around: American Foursquares” highlights early appearances of the Foursquare in such publications. For example, Lambert’s Suburban Architecture, published in 1894, features floor plans and a rendering of the residence of Geo. J. Smith, Esq., in Nutley, New Jersey. The author, William Lambert, described this new kind of house as a “straightforward” variation of the Colonial style, with “good square spacious rooms and a large attic.”

Residence of Geo. J. Smith from Lambert’s Suburban Architecture, 1894.

During the first decade of the 20th century, Chicago architects produced hundreds, if not thousands, of Foursquares. Among them was Clarence Hatzfeld, the architect of my house and those of several of my neighbors in the Edgewater Highlands neighborhood. After training under Julius Huber, an architect known for his Queen Anne and Shingle style residences, Hatzfeld became a draftsman for the Chicago Board of Education in 1901. As the board allowed its architects to moonlight, Hatzfeld soon began accepting commissions to design houses. Between 1904 and 1906, Hatzfeld prepared plans for about a dozen Foursquares on streets near the intersection of W. Highland and N. Hermitage avenues for developer William A. Taylor.

Anna Rozek and her sons Gerald and Theodore, Jr., in front of their new Foursquare home at N. Hermitage and W. Highland Avenue, ca. 1909.

The Rozeks, the family that built my house, hired Clarence Hatzfeld to design their home in 1908. He produced a two-and-a-half story structure that was originally clad in clapboard on the first story and stucco above. With a cube-shaped form, a wide front porch, a pyramidal hipped roof, and a center dormer, the original Rozek House could be considered a classic example of the American Foursquare. As is most common with Foursquares, Hatzfeld’s plan for the first floor was relatively open, featuring an archway between the living room and a room labelled “den,” as well a sliding pocket door between the den and dining room. The second story had three bedrooms and a bathroom. As explained by “Looking Around: American Foursquares,” one of the reasons that the house type is nationally significant is that it was among “the first affordable middle-class home types to feature both electricity and a standard sink-toilet-bath bathroom.”

Rozek House with its 1920s front addition. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Theodore Rozek, owner of a printing company in Chicago, and his wife, Anna, had two young sons, Gerald and Theodore Jr., when they first moved into the house in late 1908. A few years later, Anna gave birth to their third child, Eleanor. Sometime in the 1920s, the Rozeks built a new front addition to the house. They hired another Chicago architect, Andrew E. Norman, to prepare plans for the project, which expanded the living room and offered a whole new look to the house with the addition of a semi-circular front porch.

Contractor/developer Thomas E. Telfer’s Foursquare at 5540 N. Wayne Street. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Telfer developed this row of Foursquares on the 1500 block of W. Birchwood Avenue in 1912. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

American Foursquares were popular with contractors and developers because the houses were practical, relatively inexpensive to build, and well-liked by buyers and renters. Thomas Edward Telfer, a contractor/developer who had begun his career as a carriage builder, produced a number of Foursquares in Rogers Park and Edgewater on Chicago’s North Side.

Telfer purchased land on N. Wayne Avenue from John Lewis Cochran, founder of Edgewater. Telfer subdivided the large parcel and erected a stretch of four Foursquares in 1907. All of the houses were finished in stucco and had wide front porches. (Several of the porches were later enclosed.) As explained by the Edgewater Historical Society, Telfer and his family lived in the house at 5540 N. Wayne Avenue. After completing the four houses on Wayne, Telfer erected other rows of Foursquares on W. Birchwood and W. Estes avenues in in Rogers Park and on W. Hood Avenue in Edgewater.

Designed by George Maher for Harry M. Stevenson, the magnificent Foursquare at 5940 N. Sheridan Road is known as the Colvin House in honor of its second owners. Photograph by Julia Bachrach.

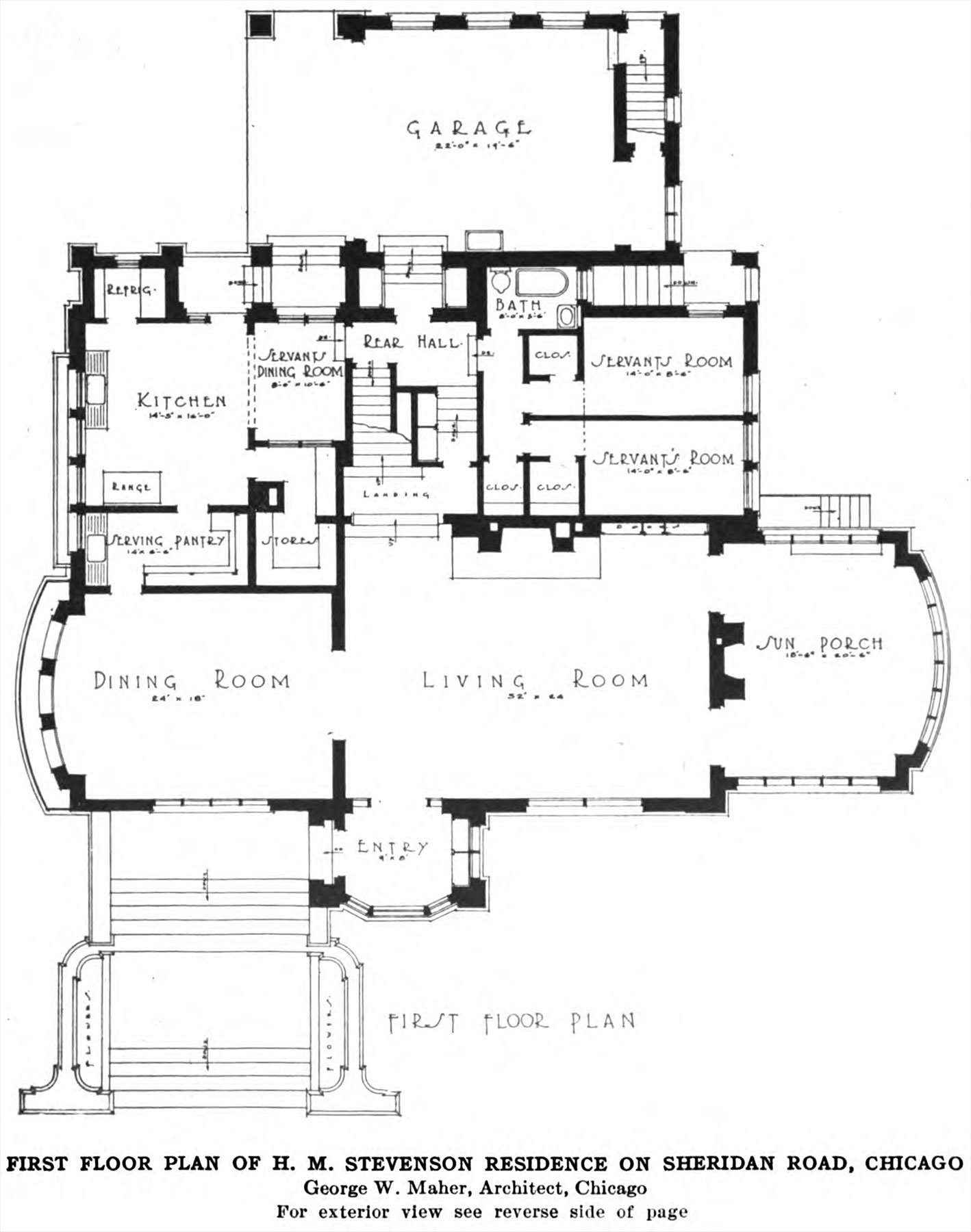

While many of the early 20th century American Foursquares were relatively modest homes, much grander versions also began to rise in these same neighborhoods, especially near the lakefront. In fact, historically, N. Sheridan Road featured a substantial collection of what might be thought of as Foursquare mansions. Among the most splendid was the Colvin House at 5940 N. Sheridan Road. Renowned Prairie School architect George Washington Maher designed the enormous residence for Harry M. Stevenson, a successful clothing merchant. He, his wife Genevieve, and their daughter Harriett lived in the house only briefly before selling it to Edwin Colvin, Vice President of the Hall Printing Company.

First floor plan for the Stevenson (now called Colvin) House at 5940 N. Sheridan Road. From Carpentry and Contracting, 1919.

Although large Foursquares like the one Maher designed at 5940 N. Sheridan Road generally had many more than four rooms per story, the floor plans were still laid out in squares of four major parts. Maher often followed the “motif rhythm theory,” meaning that he would select a decorative motif (often an image from nature) into various aspects of a design. For 5940 N. Sheridan Road, Maher chose the tulip and incorporated decorative elements inspired by that flower throughout his design. Although a later owner vastly changed the interior by adding ornate embellishments, the original layout and exterior of the grand Foursquare remain intact. A designated Chicago Landmark, the Colvin House has been restored and adapted into a special event and co-working space.

The Joseph Downey House at 6205 N. Sheridan Road is Berger Park’s south mansion. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

About three blocks north of the Colvin House, two Sheridan Road Foursquare mansions are part of what later became Berger Park. Completed in 1906, the south mansion was originally the home of Joseph Downey, an Irish immigrant who was a successful and politically connected builder. To design the home, Downey commissioned William Carbys Zimmerman, an MIT graduate who had recently been appointed as the state architect for Illinois. A massive version of a classic Foursquare, the Downey mansion is clad in buff colored Roman brick and features elegant limestone details.

The Joseph Downey House was featured in Inland Architect in August of 1906.

The Downey House’s interior is quite exquisite, with mosaic tile floors and original woodwork including built-ins with leaded glass doors. The house also originally featured a series of art glass windows by Alphonse Mucha, the famous Art Nouveau artist. Joseph Downey lived in the spacious home with his wife, Lena, her brother, Fred Klein, and an Irish servant. The couple’s chauffeur and his wife presumably resided in the large coach house behind the mansion.

Residence of Dr. C.N. Johnson, Book of the North Shore, 1910.

Stately mansions once lined both sides of N. Sheridan Road, especially in the Edgewater community. Among them were a number of spacious Foursquares. Most of these large homes were demolished between the 1950s and the 1970s to make way for apartment and condominium developments. One example was the home of prominent dentist Charles Nelson Johnson at 6118 N. Sheridan Road. Dr. Johnson’s elegant stone Foursquare was replaced by a high-rise apartment building in the mid-1950s. The demolition trend only accelerated with the rising popularity of condominiums a decade or so later.

Residence of Mr. S. H. Gunder, Book of the North Shore, 1910.

By 1980, only a handful of historic mansions remained on N. Sheridan Road in the Edgewater neighborhood. At the time, the Downey House and an adjacent Foursquare known as the Gunder House were owned by the Viatorian religious order. When the Viatorians put the properties on the market, developers clamored to replace the two mansions with a condo development. Fortunately, the Edgewater Community Council (ECC) launched a campaign to save the historic houses and surrounding greenspace and transform them into a Chicago Park District facility that would become known as Berger Park.

The Albert G. Wheeler House is now known as Piper Hall. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

In 2013, four of the surviving lakefront Foursquares were saved when the Chicago City Council designated the “Sheridan Road Mansions” Chicago Landmarks. The designation included not only the two Berger Park mansions and their coach houses, but also two nearby Foursquares owned by Loyola University. The Loyola buildings include the Albert G. Wheeler House (Piper Hall) at 970 W. Sheridan Road and the Adolph Schmidt House (Burrowes Hall) at 6331 N. Sheridan Road. Though it is a tragedy that so many impressive lakefront Foursquares fell to the wrecking ball, this small group of fine mansions provides a reminder of what the stretch of lovely homes must have been like.